Aligning the BRI with the Sustainable Development Goals: Research and Recommendations

By Rebecca Ray

After eight years of existence, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has brought significant economic gains to countries around the world by facilitating new investment, linking infrastructure networks and facilitating international trade. In parallel to this growth, China has been developing an environmental management framework to govern outbound investment and finance.

To support these continuing reforms, the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED) produces research and policy advice for China by pairing domestic and international experts on a variety of topics. For the second year, in 2021, Kevin P. Gallagher and Rebecca Ray participated in the “Green BRI and 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” CCICED task force, together with colleagues from China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). While previous years’ Green BRI reports developed frameworks and policies, this year’s special policy report focused on incorporating those policies and practices, so intentions are reflected in project outcomes. The report explored how environmental governance of China’s overseas activities is implemented, international lessons for greening the BRI and policy recommendations for China.

China’s environmental governance of overseas activities

Since the inception of the BRI, China has made significant strides toward greening its overseas activities. The special policy report tracks over 30 documents providing guidance and regulations for outbound investment and finance. Most recently, China took a significant step forward by issuing the inter-ministerial “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation,” which is the highest-level guidance that specifically advises investors and lenders to rely on international environmental standards when host-country norms are less stringent than China’s domestic regulations. This represents an advancement in environmental governance of China’s overseas activities, beyond the more general earlier guidance and statements.

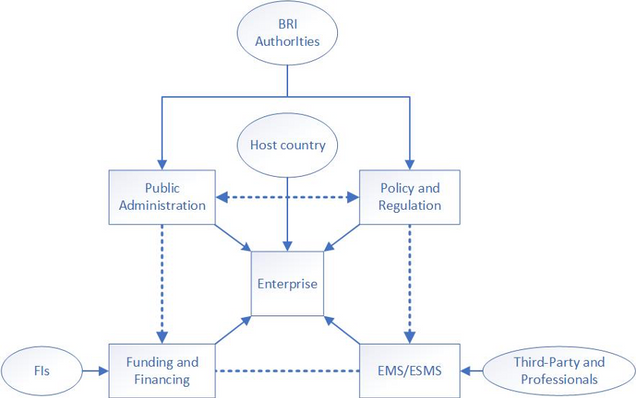

As China has developed into the world’s largest source of bilateral finance, and one of the world’s top sources of foreign direct investment, its environmental governance of overseas activities has been spread across many actors: government regulators, project sponsors and financial institutions, among others. Figure 1 below shows this ample, but fragmented approach to incorporating environmental risk management into the BRI.

Figure 1: Interconnected Environmental Governance of the BRI

Because China’s environmental governance of its overseas economic activities has grown in both robustness and complexity, now is an important time to glean lessons from other international actors for mainstreaming these concepts in project planning and implementation and streamlining the processes throughout project lifecycles.

International experiences in greening overseas development finance

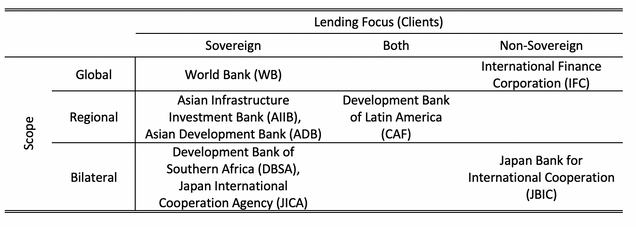

To seek lessons from other international development finance institutions (DFIs) for China, the Green BRI research team chose a variety of global, regional and bilateral DFIs from across the world, as shown in Table 1 below. The team gave particular consideration to South-South institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA). Also, as China supports private, as well as public, project sponsors around the world, the team chose DFIs that lend to sovereign and non-sovereign borrowers alike.

Table 1: Comparison Cases in Environmental Governance Practice

The team examined how each of these DFIs incorporated their policies into practices across the lifecycle of a project, in three stages: upstream project planning; assessment of project proposals; and implementation of existing projects.

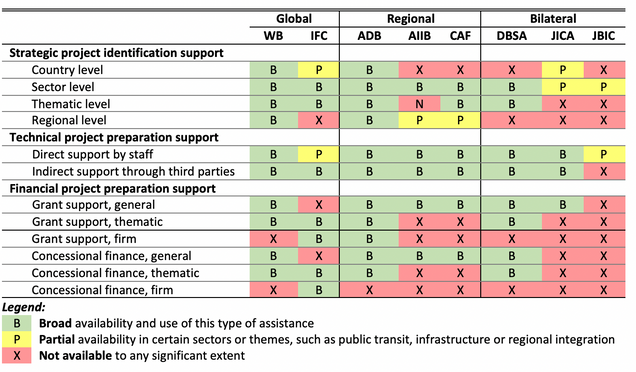

In the upstream stage of project development, DFIs have focused on three major areas for collaboration with host countries. First, long-term strategic cooperation can identify and develop broad strategies to cultivate pipelines of projects that will support local sustainable development goals. Within the context of these strategies, DFIs work closely with host country governments to develop project proposals. This step can be particularly important for new sectors with significant technical planning requirements, such as renewable energy development. Finally, where needed, DFIs may offer financial support (in the form of either grants or concessional finance facilities) for these technical planning steps.

Table 2: DFI Environmental Governance Practices in the Upstream Stage

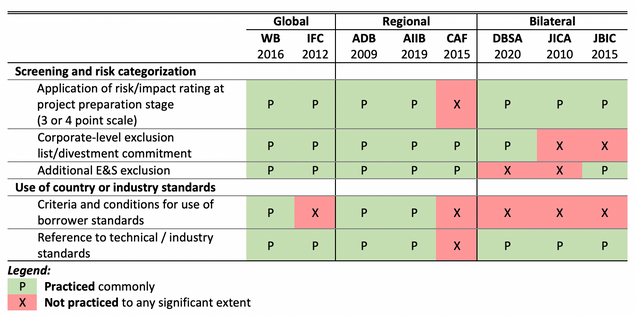

Once a project has been proposed, DFIs weigh their risk levels with a few standardized, rapid assessment tools. First, most of the DFIs studied use a broad risk-scoring mechanism to determine whether a project is likely to require higher scrutiny. DFIs also commonly use “exclusion lists” to immediately disqualify particular types of high-risk project. For example, the ADB, AIIB and JBIC have all made public statements that they will not support future coal projects. By incorporating these rules, DFIs can avoid spending time and institutional resources on projects that will likely not pass detailed scrutiny. Finally, when establishing the standards that will apply to each project, most DFIs have developed guidelines for when they should rely on host-country standards and when they should instead rely on their own standards, or those set at the global level.

Table 3: DFI Environmental Governance Processes at the Assessment Stage

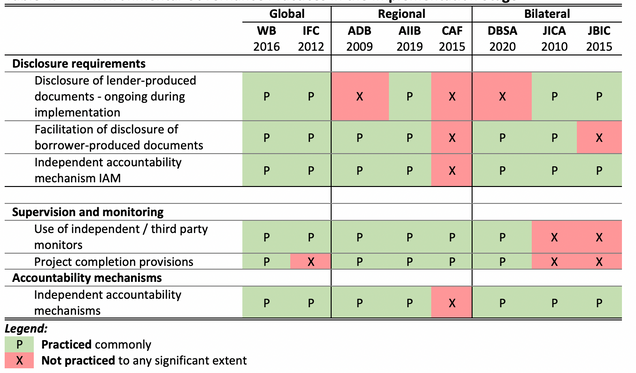

Once a project has been accepted and is being implemented, DFIs use two main approaches to ensure projects meet expectations. First, transparency of project operations can ensure that stakeholders have a shared understanding of expectations. Most DFIs also use ongoing monitoring of project operations and eventual project completion to ensure continuing performance. Finally, in the event that problems do arise, independent accountability mechanisms can resolve difficulties in early stages.

Table 4: DFI Environmental Governance Practices in the Implementation Stage

Overall, while Tables 2-4 show some variation among DFIs, they also show overwhelming consensus on the importance of a few general practices. To meet the level of this general global consensus, a DFI environmental governance system should incorporate a few simple processes:

- First, in the upstream stage, DFIs should collaborate with host countries to develop pipelines of sustainable projects.

- During project assessment, they should use risk classification systems and exclusion lists to facilitate evaluation of a wide variety of proposals.

- Once a project is underway, they should rely on transparency, monitoring and accountability to ensure projects live up to their promised performance.

Policy recommendations

As Figure 1 above shows, a wide variety of actors are involved in overseeing the environmental performance of China’s international economic activity. The concluding chapter of the special policy report outlines key recommendations for policymakers, financial institutions and project sponsors.

Policymakers can have a tremendous impact on the performance of the entire BRI community by increasing their financial and policy support for sustainable outbound investment. First, simply making more funds and guidance available will yield important results. Furthermore, in order to facilitate other actors’ ability to incorporate the above lessons, policymakers can develop a taxonomy for the sustainable investment and finance sector.

Financial institutions also have a crucial role to play, as their approvals of projects make implementation possible. The lessons in the report show the importance of two steps that are not currently widely used by Chinese DFIs: facilitating a hierarchical classification and management and developing environmental exclusion lists of sectors that they will not support, such as coal-fired power plants. Taking these two steps could help streamline environmental consideration in finance operations.

Finally, project sponsors and third-party advisors have the ultimate responsibility for project preparation and performance. Their active oversight is crucial to ensuring the BRI develops a pipeline of sustainable projects that deliver on their promises.

To help all of these actors implement these recommendations, China’s MEE has developed several important tools. For policymakers and financial institutions, MEE has developed a six-step Whole Process Assessment framework that establishes a process for project development, evaluation and oversight. For project sponsors, MEE has developed toolkits to quickly assess the likely environmental impacts of project ideas. By adopting these recommendations and available tools, Chinese policymakers, DFIs and investors have an opportunity to continue strengthening their environmental governance and developing the vision of the Green BRI.

Read the Report