Looking for the Mothers: Grief Counselors in Zambia Trying to Connect with Bereaved Parents.

A version of this article originally appeared in Faculty Opinions Blog.

“How many this weekend?” Magda Mwale asks. She is in Lusaka, Zambia, standing in a small lab behind the University Teaching Hospital morgue with her colleagues Ruth Nakazwe and Chilufya Chikoti. “Nine,” Ruth responds. Nine babies. It seems like a small number, but not when they are dead. Then every one is a heavy and urgently felt burden. “Nine too many,” Mwale responds.

A similar conversation occurs here daily. You might expect the daily evidence of loss to numb Mwale and her colleagues, build a protective shield of compassion fatigue. But the opposite is true. During the brief, solemn pause in the conversation, everyone gives themselves a mental and emotional shake. A mother and father loved each of these babies. Somewhere in Lusaka, they are reeling.

Mwale is a grief counselor based in the morgue, offering a service much needed but rarely available in Zambia. She also leads a team of four other counselors who are collecting data for a post-mortem study focused on infants who die in their first six months of life. The Zambia Pertussis/RSV Infant Mortality Estimation Study (also known as ZPRIME) set out in 2017, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to swab the nose of every infant in Lusaka who dies between the ages of 4 days and 6 months.

What did they die from? That’s the question the Zambia team and Christopher Gill, an infectious disease physician and associate professor of global health at the Boston University School of Public Health, are trying to answer. They want to know how many of these babies die with pertussis and respiratory syncytial virus, better known, respectively, as whooping cough and RSV. So far, less than one percent of the babies enrolled in the study have pertussis. But 10 percent have tested positive for RSV which comes in seasonal waves.

Enroll 3000 dead babies, swab their noses, and wait for the lab results. The study, according to Gill, is a simple matter of counting. The challenges are emotional and logistical. “We have to enroll children and get consent from parents on the worst day of their lives,” he says. “Their child has just died. This is not a particularly good time to be talking about a research study.”

Gill, Mwale, and the rest of the Zambia team knew they had to put empathy first in their effort to bridge cold science and human compassion. In consultation with Dr. Angel Chirwa, a psychiatrist based at University Teaching Hospital, they developed a detailed grief counseling protocol and script to structure their conversations with family members.

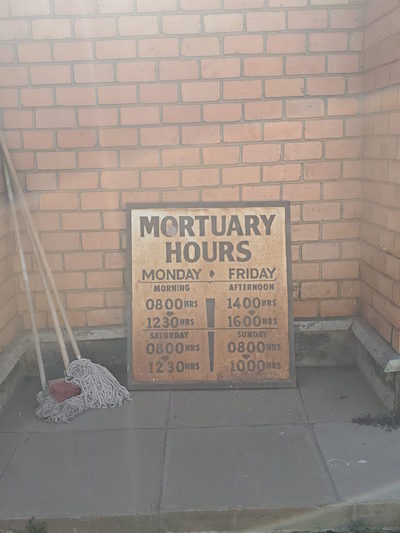

The painted sign over the morgue intake door is unflinching: BID, Brought in Dead. Families come to the low-slung concrete building to make funeral arrangements and lovingly wash the bodies of their dead. Huddled groups of women wearing white support relatives sagging from the blow of loss. The air vibrates with emotion and activity. Wailing, singing, praying, drumming, laughing. Lives celebrated and mourned. Halfway up the long driveway lined with flower merchants and funeral kiosks someone has painted “suffering tree” in black on the stone wall. Extended families on their way to burials wait in the beds of white pick-up trucks for a coffin to slide into their midst. Everything about the place defies euphemism.

“He didn’t want to come in,” Mwale says, describing a conversation she just had with a father whose baby died the day before. “The grandparents were here to collect the baby and he was waiting by the truck. I convinced him to come see her one last time. He took her in his arms and started to cry.”

Funerals in Zambia are important. Typically, they last up to a week and are a primary means of processing grief. Relatives travel long distances to close in around those left behind and carry them through. But support for parents who lose very young babies is muted and pragmatic. No one gathers. No church service precedes the burial. Mothers are kept away. Couples temporarily separate. Mothers often return to their parents’ home for cleansing rituals that can last weeks.

Fathers also stay on the periphery. Those who come to the morgue tend to linger outside. “I encourage them to come in to say goodbye,” Mwale says, “to even touch the foot or hand.” Mothers are rarely afforded such opportunities

Families are distraught, rushing to pick up the body, prepare it, and get to the graveyard. Sometimes they are angry. They blame the hospital or suspect malfeasance. Sometimes they lash out at the person in a white coat asking to talk to them.

“Our role is to bring empathy and remain neutral,” explains Charles Chimoga, who has many years of experience doing post-mortem studies. “Sometimes grieving family members are angry and blame medical staff for the death,” he says. “They sometimes say that we are just sitting there waiting for dead babies to test. That what we are doing now should have been done when the baby was still alive. We do not react or get defensive. We listen, empathize, and explain that what we are doing is unconnected to the child’s death. If they don’t believe us we don’t push. We continue to offer emotional support.”

Approaching families to offer condolences and explain the study is a delicate, intricate interaction. If the family agrees to participate, the counsellors ask for consent to swab their baby’s nose. For infants who die at home or en route to the hospital, they also record death narratives, known as verbal autopsies, about the events leading up to the final breath. Mostly families are willing to participate as long as the process doesn’t take more than a few minutes. (The consent rate hovers around 85 percent.) If a family does not consent, counselors continue the conversation as long relatives want to talk.

Nine babies this weekend. Four on Monday. Two on Tuesday. Three on Wednesday. Five on Thursday. Twenty to thirty dead babies each week. As the number of samples clicks unrelentingly upward, these grief counselors-cum-researchers feel compelled to do more.

The few moments of comforting talk with extended family members under a shady canopy behind the BID are not enough. The team knows parents ache out of sight, just beyond their reach. Culture and pragmatic resignation create formidable impediments to connecting with bereaved mothers and fathers.

The few moments of comforting talk with extended family members under a shady canopy behind the BID are not enough. The team knows parents ache out of sight, just beyond their reach. Culture and pragmatic resignation create formidable impediments to connecting with bereaved mothers and fathers.

Zambian cultural traditions prohibit parents from openly mourning very young babies, this is especially true for young, first-time mothers. Nothing good, mothers are told, will come of dwelling too long and too openly on the baby who has died. Showing and holding too much sorrow for the one who has left can block another from coming. “We have an inner belting that allows us to not be expressive,” Mwale says.

Infant mortality statistics hint at the reason for this learned emotional restraint. Forty-five of every 1000 babies born alive in Zambia die before their first birthday. Forty-five is an ongoing travesty, especially when compared to 6 in 1000 in the US or 0.7 in Iceland. But it’s also an achievement, down from 109 in 1996.

Despite the progress, the unfair truth remains: Zambian women cannot be surprised when their babies die. But grim statistics do not reduce the pain. On the contrary, the death of a child adds grief to the mountain of other stressors created by poverty. Vulnerability begets vulnerability. The parents of the babies enrolled in the ZPRIME study are often young, many just teenagers from the poorest parts of Lusaka. Some mothers are already experiencing post-partum depression, compounded by grief and, possibly, feelings of guilt.

The grandmothers and aunties who come to the BID assure the counseling team that the bereaved mother will get over her loss quickly with family support. The team expects this answer, but they know emotional responses are being stifled by well-meaning elders. Young mothers who show their devastation are quickly hushed by older women who buried their own babies long ago. Who had even more reason to expect death to come in the night in the form of diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, or for no apparent reason at all.

These traditions likely began as a form of protection, a sanctuary from grief, and a road map for moving on. But they also isolate young mothers and fathers and can deepen pain rather than healing it.

“For the mother, the story behind the pregnancy, emotions, and feelings of attachment to her child are ignored,” says Chirwa. “The mother must move on very quickly. She must not expose herself and her misfortune to the world. The father is often also lost in the equation. It’s life and these things happen.”

Gertrude Munanjala, another member of the counseling team, describes the compound trauma of being forced to move on too quickly: “A baby is a baby. In maternal and child health we start counting a baby from the time you conceive. You’re pregnant, you’re talking to your baby in the tummy because you believe you are going to have that baby. This baby came out, breathed, cried, and you breastfed. That’s a baby. So nothing should stop you from grieving over something you have held in your hand. Something that was growing in me. I have held it in my hands and then it goes away. Please allow me some time to grieve.”

The team recently started reaching out to parents after the child’s burial. Their goal is to give parents an opportunity to express emotions their friends and family have been telling them to hide. The counselors understand that the symptoms of complex grief and depression are expressed in many ways. When asked what formal grief counseling offers that the community cannot, each counselor emphasizes the importance of asking bereaved parents specific questions about their sleep, their dreams, whether or not they are eating, their social interactions, and relationship with their spouse.

“Those institutions like the church, the old women, the uncles, the grandmas will not see,” says Benard Ngoma. “We see families breaking down. Others where, since the death of the child, the husband and wife are no longer together because they are blaming each other.” Grief counseling, he explains, brings all of this to the surface before it festers and causes greater damage.

Sometimes opening up is enough. In other situations, counselors can provide medical referrals. This happened in one of Munanjala’s sessions with a couple who told her that they wanted to wait before trying for another baby. She referred them to a clinic where they could learn about family planning options and suggested they go together.

Counseling has been available in a limited way for decades in Zambian healthcare facilities, according to Chimoga, who specialized in psychiatry when he was training to become a clinical officer in the 1970s. But over the last 20 years HIV care absorbed many trained counselors. In a context where counselors, psychiatrists, and resources for mental health care are few, helping people move through grief has never been a health system priority.

The team recently set up a comfortable, quiet counseling room in their office across Nationalist Road from the morgue. And they have begun distributing pamphlets about grief counseling describing what it is, how it is useful, and how to get help. They put a stack in the neonatal intensive care unit, where half of the babies enrolled in the study die (the other half die at home or on the way to the hospital). In the morgue, they ask family members to take the pamphlet home and let bereaved parents know that someone will be contacting them. Within a week, the counselors call parents and invite them to come in for a conversation, on their own or with their spouse. The session is free and transportation is reimbursed.

So far, they have held five counseling sessions. Every week they schedule more, but they have recently had a number of clients not show up, even after confirming the appointment. The team is disappointed, but they are not surprised. They know they are offering a service that can appear culturally counter-intuitive. Asking grieving parents to travel to talk about their feelings with strangers, they all acknowledge, goes against the grain of quiet fortitude and family connection. “It would be better if the parents met us,” says Chimoga. “An emotional bond and trust could be established.”

Timing is critical. “If the mother has gone off to her parents’ house for a month,” Chimoga says, “and comes back feeling better, we should not interfere.” Offering counseling too late, he explains, runs the risk of reopening wounds that will be even more difficult to heal a second time. “If we can reach the parents within the first week after the baby has died,” he says, “then we can offer useful support.”

It’s a fragile balance: offering therapy when it can be beneficial, recognizing early signs of recovery or complex grief, and navigating deeply engrained cultural practices. “We are all learning as we go,” says Lawrence Mwananyanda, ZPRIME co-principal investigator, who oversees the Zambia field operations.

So far the team has enrolled over 1500 infants in the study. Each tiny nose they swab, jolts their sense of urgency. Three thousand devastated mothers and fathers grieve silently. “Looking at the few families or couples I have met at the BID,” says Ngoma, “I can see that a father or mother is going into depression. I will see this mother is not really attended to. You can see that they need help. They don’t come back but we know if they had we could have helped.”

The team is now looking into the possibility of visiting mourning parents at home. They think home visits will inspire trust and willingness to open up. As evening draws in, Chimoga and Ngoma walk away from the BID, past the suffering tree and the coffin and flower vendors. They are convinced that visiting bereaved parents in their homes is the most culturally appropriate way. “As Africans,” Ngoma says, “this is what we should be doing.”

Jennifer Beard is a clinical associate professor of global health at the School of Public Health and associate editor of Public Health Post.