Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 18

Attitudes of Nurses and Physicians Towards Nurse-Physician Interprofessional Collaboration in a Tertiary Hospital in Somalia: Cross-Sectional Study

Authors Osman IM , Mohamud FA , Hilowle FM , Sahal Snr SM , Hassan II, Haji Mohamud RY , Ali TA, Barud AA

Received 8 December 2024

Accepted for publication 9 April 2025

Published 14 April 2025 Volume 2025:18 Pages 2075—2082

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S511008

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Iftin Mohamed Osman,1 Fartun Ahmed Mohamud,1 Fartun Mohamed Hilowle,1 Said Mohamud Sahal Snr,2 Iman Ilyas Hassan,3 Rahma Yusuf Haji Mohamud,3 Tigad Abdisad Ali,4 Asha Abdullahi Barud5

1Department of Education at Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia; 2Department of Health Care Service at Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia; 3Department of Nursing at Mogadishu Somalia-Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia; 4Department of Infection Prevention Control, Mogadishu-Somalia-Turkiye Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia; 5Department of Anesthesia at Mogadishu Somalia-Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia

Correspondence: Iftin Mohamed Osman, Email [email protected]

Background: Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) between nurses and physicians is essential for improving patient outcomes, healthcare efficiency, and professional satisfaction. However, in Somalia’s resource-limited healthcare system, deeply rooted hierarchies, inadequate interprofessional education, and systemic constraints hinder effective collaboration. This study examines the attitudes of nurses and physicians toward IPC in a tertiary hospital, shedding light on challenges and opportunities for enhancing teamwork and patient care in this context.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at a tertiary hospital, targeting nurses and physicians with a minimum of six months of clinical experience. Given logistical and accessibility constraints, a nonprobability convenience sampling approach was used to select 258 participants. Data were collected through a validated, self-administered questionnaire adapted from the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes toward Nurse-Physician Collaboration. After accounting for incomplete responses, the final sample size was 250. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted to assess attitudes and associated factors.

Results: Most participants (88.8%) acknowledged that shared education fosters better role understanding, while 87.6% emphasized the value of collaborative training. A statistically significant difference was observed in perceptions of physician authority (p = 0.039), with nurses demonstrating a higher recognition of physician leadership. However, no significant differences emerged regarding shared education (p = 0.293), the balance between caring and curing (p = 0.208), or nurse autonomy (p = 0.453). These findings highlight prevailing hierarchical structures and the potential for improved interprofessional training.

Conclusion: While overall attitudes toward IPC were positive, entrenched hierarchical norms and differing perceptions of authority remain significant barriers to effective collaboration. Addressing these challenges requires structured interprofessional education programs, policies promoting role equity, and hospital-wide initiatives to foster a culture of teamwork. Strengthening IPC in Somalia’s healthcare system could enhance patient care, optimize resource utilization, and improve professional satisfaction in a setting where collaborative practice is crucial for overcoming systemic limitations.

Keywords: interprofessional relations, physician-nurse relations, attitude of health personnel, surveys and questionnaires, JSAPNC

Introduction

Healthcare systems worldwide increasingly recognize the importance of inter-professional collaboration (IPC) in improving patient outcomes, healthcare efficiency, and professional satisfaction. IPC is a process where healthcare professionals, such as nurses and physicians, work collaboratively to provide comprehensive care, leveraging their distinct expertise while fostering mutual respect and shared decision-making.1,2

In Somalia, the healthcare system faces unique challenges due to years of political instability, resource limitations, and inadequate health infrastructure. These factors exacerbate the need for effective collaboration among healthcare workers to address pressing health issues. Nurses, who form the backbone of primary healthcare delivery, must work closely with physicians to improve care delivery. However, hierarchical barriers, limited professional autonomy, and insufficient inter-professional training can hinder collaboration. Similar challenges have been documented in other African nations, such as Ethiopia, where studies reveal that while nurses demonstrate positive attitudes toward collaboration, physicians often hold dominant roles, leading to imbalances in teamwork.2,3 The relationship between physicians and nurses in Somalia, like in many other settings, is hierarchical, with physicians traditionally holding higher authority and nurses perceived as assistants rather than partners in patient care. This imbalance can undermine the effectiveness of collaboration, as nurses may feel disrespected or lack autonomy in decision-making processes. In such environments, the lack of inter-professional communication and mutual respect may lead to conflicts, medical errors, and negative outcomes for patients.1,4

Despite these challenges, the importance of inter-professional collaboration cannot be overstated. Studies have shown that collaboration between nurses and physicians improves patient outcomes, reduces healthcare costs, enhances job satisfaction, and ensures patient safety.5 However, inadequate communication or miscommunication between healthcare professionals can lead to persistent conflict, which has been linked to higher turnover rates among nurses and contributes to the global nursing shortage.6,7 Moreover, research has shown that physicians and nurses often view collaboration differently. Nurses tend to see it as a partnership where both contribute equally, while physicians may see it more as following orders and guidelines.4,8

Despite the critical role of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in healthcare, there is a lack of research on nurse-physician collaboration in Somalia’s resource-limited and hierarchical healthcare system. Existing studies primarily focus on well-resourced settings, leaving a gap in understanding how IPC functions in Somali hospitals, particularly in tertiary care. While hierarchical structures, communication barriers, and limited interprofessional training are recognized challenges in other contexts, their specific impact in Somalia remains underexplored. Additionally, the role of interprofessional education (IPE) in shaping collaborative attitudes has not been adequately examined. This study addresses these gaps by assessing nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of IPC, identifying key challenges, and proposing targeted interventions to enhance collaboration in Somalia’s healthcare system.

Methodology

Study Area

The study will be conducted at the Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital, one of the largest teaching and referral hospitals in Somalia. This institution provides advanced healthcare services, including inpatient and outpatient care, surgery, maternal and child health services, and training for healthcare professionals. This setting hospital provides a diverse working environment for healthcare professionals, making it suitable for examining inter-professional collaboration.

Study Design

A cross-sectional descriptive study design will be employed to assess the level of collaboration and its associated factors among nurses, and physicians.

Study Population and Sampling

The target population includes nurses, and physicians working in the hospital. Inclusion criteria involve professionals with a minimum of six months of experience in their respective roles to ensure sufficient exposure to collaborative practices. Nonprobability Convenience Sampling will be used to select participants. This method involves selecting participants who are readily available and willing to participate.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size for this study was determined using the formula for estimating a single population proportion. Assuming a 95% confidence level Z = 1.96, a proportion (p) of 0.5, and a margin of error of 5%, the initial sample size was calculated to be 384. Given the study population size of 489, the finite population correction formula was applied, resulting in a final adjusted sample size of 215. To account for potential non-responses, 20% of the calculated sample size was added, bringing the total sample size to 258. After data collection, eight participants were found to have missing data, resulting in a final sample size of 250 participants included in the analysis.

Data Collection and Adaptation of JSAPNC

A structured self-administered questionnaire was administered between March 24, 2024, and December 8, 2024, to evaluate attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration. The primary instrument was the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Nurse-Physician Collaboration (JSAPNC), which has been widely validated in diverse healthcare settings. For this study, the original JSAPNC was administered without modifications, ensuring consistency with its established structure and scoring system. The tool comprises four subscales:

- Shared education and teamwork

- Caring vs curing

- Nurses’ autonomy

- Physician dominance

Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting more positive attitudes toward collaboration. To contextualize the findings, additional items were included to capture socio-demographic characteristics, professional roles, and years of experience. While no modifications were made to the JSAPNC, a pilot test was conducted to ensure clarity, feasibility, and cultural appropriateness for the study population. The strong reliability and validity of the JSAPNC in previous studies support its applicability in this research.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the relevant ethics committee at Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital. The approval reference number is MSTH/17421. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, and written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. Confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were ensured throughout the study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics will summarize demographic and professional characteristics. The mean scores of collaboration attitudes will be compared using independent sample t-tests or ANOVA for groups (nurses and physicians) with statistical significance of 5%.

Results

The majority of healthcare professionals are physicians, representing 54.8% of the workforce, while nurses make up 45.2%. In terms of gender, 64.8% are male, while 35.2% are female. The age distribution shows that the workforce is relatively young, with most individuals aged between 20 and 39 years. Specifically, 54.0% fall into the 20–29 years, while 45.2% are between 30 and 39 years, and only 0.8% are in the 40–49 age group. In terms of experience, nearly 90% of the professionals have less than 10 years in the field, indicating a predominantly early-career workforce.

Educational qualifications are largely centered on bachelor’s degrees, which account for 70.0% of the workforce, followed by 26.8% holding master’s degrees, and a small 3.2% with a diploma. For nurses, the working areas vary, with the largest proportion assigned to ICU services (15.6%), and followed by 10.0% in other unspecified areas, 8.0% in the operating room, 7.2% in inpatient care services, and 4.4% in emergency services. Among physicians, work areas are mainly divided between surgical departments (29.2%) and internal medicine (21.2%), with a smaller group (4.4%) working in basic sciences (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic and Professional Characteristics of Healthcare Workers |

In Table 2 the study provides insights into healthcare workers’ attitudes toward collaboration between nurses and physicians in a tertiary hospital.

|

Table 2 Attitudes Toward Interprofessional Collaboration |

Most healthcare workers believe in the importance of teamwork between nurses and physicians during their education, with 88.8% agreeing or strongly agreeing that this helps them understand their respective roles. Similarly, 87.6% feel that interprofessional relationships should be part of their training. A strong majority, 73.6%, see nurses as collaborators and colleagues rather than as assistants to physicians, and 86% agree that there are overlapping areas of responsibility between the two roles. Additionally, 87.2% believe that physicians should be educated to establish collaborative relationships with nurses.

Regarding patient care, 60.4% of respondents think that both physicians and nurses should contribute to decisions about patient discharge, while 78.4% feel that nurses should also be responsible for monitoring the effects of medical treatments. Many agree (82.4%) that nurses are qualified to address patients’ psychological needs and provide emotional support. Furthermore, 84% believe nurses should be involved in policy decisions that affect their working conditions, and 83.2% feel that nurses should have a say in policies concerning support services that impact their work.

When it comes to accountability, a substantial 86% believe that nurses should be accountable to patients for the care they provide. On the other hand, opinions are divided on whether the nurse’s primary role is to carry out physicians’ orders, with only 62.4% agreeing strongly, and 37.6% disagreeing to some extent. Similarly, there is a split regarding the belief that doctors should hold the dominant authority in healthcare matters, with 63.2% supporting this view but still a notable proportion disagreeing.

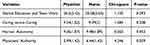

Physicians and nurses scored very similarly when it came to the importance of shared education and teamwork, with averages of 20.6 for physicians and 20.58 for nurses. Since the significance level (p = 0.293) is above 0.05, this difference is not statistically significant, meaning both groups likely agree on the importance of these aspects.

When it comes to the balance between caring for patients and curing them, the scores are again close, with physicians averaging 9.34 and nurses 9.39. Here too, the significance level (p = 0.208) suggests no real difference in how they view this balance, showing that both groups value these aspects similarly.

On the topic of nurses’ autonomy, physicians scored an average of 9.36, while nurses scored slightly higher at 9.48. The significance level (p = 0.453) shows no significant difference here either, suggesting that both groups have similar views on the independence nurses should have in their roles (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Significant Differences in Perception Regard Nurses and Physicians Workplace |

However, when it comes to views on physician authority, physicians scored an average of 5.99, while nurses scored 6.44. This time, the significance level (p = 0.039) is below 0.05, indicating a significant difference in how each group views physician authority. Nurses rated physician authority slightly higher, which might mean that nurses expect or acknowledge a stronger leadership role from physicians in certain situations.

This small difference could reflect traditional roles in healthcare, where nurses may see physicians as the main decision-makers, especially in complex cases. Physicians, on the other hand, may view themselves as part of a more collaborative team with shared authority. This gap suggests that while physicians might feel they are moving towards more collaborative practices, nurses may still perceive physicians as having a stronger role in decision-making.

Discussion

This study presents a diverse demographic and professional profile of healthcare professionals, with physicians constituting the majority of the sample at 54.8%, followed by nurses at 45.2%. This proportion aligns with global trends that show a higher number of physicians in hospital settings to address diverse and complex medical needs.9,10

Gender-wise, males represent 64.8% and females 35.2%, reflecting a male-dominated healthcare environment. This aligns with previous findings in countries with gender disparities in healthcare, where fewer females pursue healthcare careers due to sociocultural and structural barriers.11,12

Education levels show that 70% of professionals hold a bachelor’s degree, 26.8% have a master’s, and a small fraction possess a diploma. Similar educational trends are reported across healthcare sectors, suggesting a shift towards higher qualifications as the standard for clinical roles.9,12,13

Among nurses, ICU services employ the largest proportion, indicating the critical need for specialized nursing care in high-dependency units. For physicians, work areas like surgical (29.2%) and internal medicine (21.2%) dominate, reflecting the high demand for these specialties in tertiary care settings.10,11

Our study found that 88.8% of respondents agree that team-based education fosters role understanding, and 87.6% support including interprofessional relationships in training. Similar findings are reported in studies where structured interprofessional education has been linked to enhanced collaborative skills and mutual respect between professions.12,14 Furthermore, the majority believe in the collaborative role of nurses as colleagues rather than assistants (73.6%), reinforcing the shift toward a more egalitarian healthcare model.11

Attitudes toward decision-making in patient discharge and treatment monitoring (60.4% and 78.4%, respectively) reflect an openness to shared responsibility, aligning with global research that emphasizes collaborative decision-making as a key factor in improving patient outcomes.15

Additionally, accountability in nursing is strongly supported, with 86% agreeing that nurses should be accountable to patients, underscoring a shift towards professionalism and autonomous practice in nursing roles.16

The belief that nurses should contribute to policy decisions, as supported by 84% of respondents, reflects an evolving recognition of nurses’ influence on healthcare policies.17 Meanwhile, 62.4% of respondents believe that nurses’ primary role is to follow physicians’ orders, suggesting that while traditional hierarchies persist, there is an ongoing shift towards more collaborative, shared decision-making in clinical practice.16

The shared perception of education and teamwork as essential to effective healthcare is strongly reflected in the similar scores between physicians 20.6 and nurses 20.58. This similarity, with no statistically significant difference p = 0.293, reinforces the idea that both groups recognize the value of interprofessional collaboration. According to,16 shared educational experiences and teamwork raise understanding between healthcare roles, promoting patient-centered care and justifying misunderstandings often found in hierarchical settings. This mutual emphasis on collaborative learning aligns with findings from,10 which highlight that teamwork in educational contexts builds respect and simplifies collaboration in clinical environments.

Regarding the balance between caring and curing, both physicians 9.34 and nurses 9.39 scored closely, with no significant difference p = 0.208, indicating that both groups place similar value on the dual aspects of healthcare. This alignment reflects findings from,11 who reported that both physicians and nurses embrace a holistic view of patient care, recognizing compassion and technical care as equally essential for achieving optimal outcomes.

When examining nurse autonomy, both physicians 9.36 and nurses 9.48 showed closely aligned scores, with no significant difference p = 0.453. This suggests that both groups recognize the importance of nurses having a certain degree of independence in their roles. Research by18 supports this view, showing that autonomy in nursing enables efficient decision-making and enhances nurses’ confidence, particularly in patient management and rapid response situations.

However, a significant difference was observed regarding perceptions of physician authority, where physicians scored an average of 5.99, and nurses scored 6.44, with p = 0.039. This result suggests that nurses might view physician authority as more prominent than physicians do themselves, perhaps acknowledging physicians’ leadership roles, particularly in complex cases. This finding is in line with,11 who report that nurses often see physicians as primary decision-makers, especially in specialized areas where expert judgment is critical. Meanwhile,16 suggest that physicians may increasingly view themselves as part of a collaborative team, which may not always align with nurses’ traditional perceptions of hierarchical roles in decision-making.

Limitations

This study has several limitations related to sampling bias and generalizability. The use of non-probability convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, as participants were selected based on availability and willingness, potentially limiting the representativeness of the findings. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single tertiary hospital, which may not reflect interprofessional collaboration attitudes across different healthcare institutions, such as smaller hospitals, primary care centers, or private facilities in Somalia. The exclusion of other healthcare professionals, such as midwives, pharmacists, and allied health workers, further limits the comprehensiveness of the study’s findings. Moreover, reliance on self-administered questionnaires raises the possibility of response bias, where participants may have reported more favorable attitudes toward collaboration than they actually practice. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into nurse-physician collaboration in Somalia’s largest tertiary hospital, and future research should consider probability sampling methods, multi-center studies, and qualitative approaches to enhance representativeness and depth.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the significant role of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in improving healthcare delivery, particularly in a resource-limited setting like Somalia. Most healthcare professionals, including nurses and physicians, displayed positive attitudes toward teamwork, shared decision-making, and mutual respect. The findings underline the necessity of interprofessional education as a tool to foster better understanding of roles and responsibilities.

However, challenges remain, such as hierarchical barriers and differences in perceptions of authority. While many nurses view themselves as collaborators, the persistence of traditional hierarchies may limit their autonomy. Addressing these barriers is crucial to ensuring a more balanced and effective partnership between nurses and physicians.

Overall, the results demonstrate that promoting collaborative practices can lead to improved patient care, enhanced professional satisfaction, and a more cohesive healthcare system. By focusing on education, communication, and equitable policies, the potential of IPC can be fully realized, even in challenging healthcare environments.

Recommendations

- Implement Structured Interprofessional Education (IPE) Programs: Integrate joint training for nurses and physicians in academic curricula and continuing professional development (CPD).

- Establish Clear Policies for Shared Decision-Making: Define collaborative roles and responsibilities to ensure equitable contributions in patient care.

- Conduct Communication and Conflict Resolution Workshops: Provide structured training to enhance teamwork, active listening, and conflict resolution skills.

- Strengthen Nurses’ Autonomy and Leadership Opportunities: Support nurses in supervisory roles, hospital committees, and policy development.

- Implement Continuous Assessment and Feedback Mechanisms: Regularly evaluate collaboration practices through surveys, audits, and feedback sessions.

- Tailor Interventions to Cultural and Organizational Contexts: Align strategies with local healthcare dynamics to ensure effective and sustainable improvements.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Amsalu E, Boru B, Getahun F, Tulu B. Attitudes of nurses and physicians towards nurse-physician collaboration in northwest Ethiopia: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2014;13(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12912-014-0037-7

2. Kaifi A, Tahir MA, Ibad A, Shahid J, Anwar M. Attitudes of nurses and physicians toward nurse–physician interprofessional collaboration in different hospitals of Islamabad–Rawalpindi Region of Pakistan. J Interprof Care. 2021;35(3):329–338. doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1853079

3. Melkamu E, Woldemariam S, Haftu A. Inter-professional collaboration of nurses and midwives with physicians and associated factors in Jimma University specialized teaching hospital, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):33. doi:10.1186/s12912-020-00426-w

4. Cordero MAW, Alghamdi R, Almojel S, et al. Physicians and nurses attitude towards physician-nurse collaboration in Saudi government hospitals. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;96:104649. doi:10.1002/nop2.756

5. Sayed K, Sleem W. Nurse-physician collaboration: a comparative study of the attitudes of nurses and physicians at Mansoura University Hospital. Life Sci J. 2011;8(2):140–146.

6. Alghamdi R, Alhifty E, Almojel S, Cordero MAW, Khired Z. Physician-nurse collaboration: the importance of effective communication. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021;15(3):14–18. doi:10.15171/jcs.2019.016

7. Gattan SK, Alwalani SA, Alsallum FS, Banakhar MA, Samarkandi RA, Samarkandi RA. Nurses’ and physicians’ attitudes towards nurse-physician collaboration in critical care. Glob J Health Sci. 2019;12(1):149–157. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v12n1p149

8. Grol R, Wensing M. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. BMJ. 2019;328(7434):1383–1387. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7434.1383

9. Elsous A, Alghamdi M, Al-Mugti H, Lakeman P, Henneman L, Cornel MC. Exploring factors affecting inter-professional collaboration among healthcare workers in primary health care centers in the Gaza Strip. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:146. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2083-8

10. Karki A, Thapa S, Thulung B. Attitude towards collaborative care among nurses and physicians at a teaching hospital, Chitwan. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2018;8(26):47–53. doi:10.3126/jcmc.v8i4.22191

11. Jassim AF, Alabrahemi H, Obaid KB. A study to assess perception of nurses and physicians towards their collaboration in pediatric hospitals. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S4):5726–5736. doi:10.53730/ijhs.v6nS4.9839

12. Cordero D, Karki B, Kim M. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on teamwork and collaboration in primary healthcare. J Healthc Qual Res. 2018;33(4):234–245. doi:10.1016/j.jhqr.2018.03.006

13. Ghonaim M, Davis J, Kim S. Professional practice and collaboration among healthcare professionals. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2019;13:42–50.

14. Kaifi BA, Arora S, Abdel-Razig S. Promoting inter-professional education for improved healthcare collaboration. Int J Med Educ. 2021;12:31–39. doi:10.5116/ijme.60c4.f5d2

15. Hussein AHM. Relationship between nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of organizational health and quality of patient care. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20(10):634. doi:10.26719/2014.20.10.634

16. Shields HM, Pelletier SR, Zambrotta ME. Agreement of nurses’ and physicians’ attitudes on collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic using the Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:905–912. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S370912

17. Davis J, Arora S, Shields M. Nurses’ roles in healthcare policy and advocacy. Health Policy Res J. 2022;28(3):150–160.

18. El Sayed N, Sleem W. Autonomy in nursing: a comparative study. J Nurs Res. 2011;19:93–100.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.