Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 18

Clinical Efficacy of Acupuncture in the Treatment of Uterine Contraction Pain Post-Cesarean Section: Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial

Authors Deng Y, Li Z, Zhang T, Tang X , Luo Y, Li Q, Zhang S, Liu Z , Tang D, Ai Z, Guo T , Liang F

Received 29 March 2025

Accepted for publication 17 June 2025

Published 28 June 2025 Volume 2025:18 Pages 3263—3274

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S531188

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Houman Danesh

Yuanzheng Deng,1,* Zhengping Li,2,* Tiankui Zhang,3,* Xin Tang,1 Yan Luo,4 Qifu Li,5 Shumin Zhang,1 Zili Liu,1 Diwei Tang,1 Zhenghai Ai,6 Taipin Guo,1 Fanrong Liang5

1School of Second Clinical Medicine/The Second Affiliated Hospital, Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine, Kunming, People’s Republic of China; 2Traditional Chinese Medicine Department of Preventive Care, Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhaotong, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhaotong, People’s Republic of China; 4Department of Obstetrics, Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhaotong, People’s Republic of China; 5College of Acupuncture and Tuina, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China; 6Department of Internal Medicine, Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhaotong, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Taipin Guo, School of Second Clinical Medicine/The Second Affiliated Hospital, Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine, Kunming, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 18487272658, Email [email protected] Fanrong Liang, College of Acupuncture and Tuina, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 13608058216, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Uterine contraction pain post-cesarean section (UCPCS) is one of the main complaints for mothers in the early stages of the puerperium. Acupuncture, a non-pharmacological therapy, has shown sound analgesic effects with almost no toxic side effects. This study uses acupuncture as an intervention and aimed to provide strong evidence for the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in treating UCPCS.

Patients and Methods: This single-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted at the Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China. Participants (138) are randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either an observation or control group following cesarean section. Both groups receive routine postpartum care, the control group with sham acupuncture and the observation group with conventional acupuncture for 3 days. The primary outcome is the mean Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score of the UCPCS. Secondary outcomes include the mean of UCPCS intensity, frequency, total duration, number of days to disappear, amount of vaginal bleeding and lactation, time to first lactation, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score. The final results will be analyzed in accordance with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle using SPSS V.28.0.

Discussion: This is the first RCT using non-penetrating sham acupuncture as a control to validate the clinical efficacy of acupuncture for UCPCS. The results of this study are expected to provide an effective therapeutic option for UCPCS, as well as offer clinicians and researchers strong evidence regarding non-pharmacological interventions.

Keywords: uterine contraction pain post-cesarean section, acupuncture, protocol, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

The global cesarean section rate has continuously increased over the years, particularly in Asian countries.1 China’s cesarean section rate reached 43.4% in 2019, significantly exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommended level.2 As this rate climbs, postoperative pain is drawing increasing attention. Uterine contraction pain is a non-negligible component of pain in the early postoperative period. Uterine contraction pain post-cesarean section (UCPCS) is characterized by intermittency, uncertainty of position, and short duration.3 Postpartum lactation stimulation and the use of contraction-type medications can further exacerbate uterine contraction pain.4,5 When UCPCS occurs, it not only disturbs the mother’s daily activities and quality of sleep, but also causes the mother to resist breastfeeding due to the pain, which directly affects the newborn’s nutritional intake. In the long term, if not effectively dealt with, in addition to slowing the uterine recovery process, it may induce chronic pain, postpartum anxiety or depression, posing an ongoing threat to the health of mother and child.3,6,7

Both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches serve as vital elements in the management of UCPCS.8,9 Local hot compress is the most widely used non-pharmacological therapy in clinical practice and is effective in relieving uterine cramping, but its efficacy of analgesia is relatively mild. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most widely used pharmacologic therapy for postpartum analgesia. However, evidence does not support it as the safest and most effective oral analgesic option.10 Although diclofenac sodium suppositories, a commonly used type of NSAIDs, could reduce the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects, they can still cause nausea and vomiting.11 Therefore, finding safe and effective therapies is also significant.

Acupuncture is a safe, non-pharmacological therapy that has been shown to reduce or eliminate various types of pain.12,13 Studies have shown that acupuncture can alleviate the severity of UCPCS, reduce the frequency of episodes, shorten pain duration, and promote postpartum recovery.14,15 However, many studies did not blind participants, making it difficult to rule out a placebo effect. The clinical efficacy of acupuncture for treating UCPCS still requires further validation. We thus designed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to validate the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in UCPCS using non-penetrating sham acupuncture as a control.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design and Setting

This single-blind RCT is being conducted at the Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China. A total of 138 participants are being recruited and randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either an observation or control group. Each participant receives six acupuncture treatments over three consecutive days and follow-up for 2 weeks. The study protocol is designed in strict accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials 2013 (SPIRIT 2013) (Supplementary Material 1) and adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.16 This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (LD2024-002) and registered with the China Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400086062). The study design flow chart is presented in Figure 1, and the registration, intervention, and evaluation timeline is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Timeline for Enrolment, Intervention, and Evaluation |

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of study design. |

Participants

Recruitment and Informed Consent

All participants will be recruited via posters displayed in the obstetrics department. A senior obstetrician will initially screen enrollees before a scheduled cesarean section and provide a detailed introduction to the study process, the rules to follow, and the benefits and potential risks of participation. After a cesarean section, the team will conduct further screening, and eligible participants will sign an informed consent form (Supplementary Material 2) for formal enrollment. Participants can withdraw from the study at any time, for any reason, with no risk of losing benefits.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants must meet the following criteria: (1) cesarean section; (2) age ≥18 years; (3) pregnancy duration between 37 and 42 weeks; (4) single and live birth; (5) intent to breastfeed; (6) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Classification I or II; and (7) ability to participate in the clinical study and actively provide informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria

Participants who met any of the following criteria will be excluded: (1) severe complications during pregnancy or childbirth; (2) history of uterine or pelvic pain; (3) psychological disorders or mental illnesses, emotional abnormalities, inability to understand and express research-related issues adequately; (4) long-term use of analgesic medications; (5) allergic to acupuncture or skin abnormality at the site of needling; (6) allergic to or contraindications for use of NSAIDs; or (7) participation in other studies.

Other Criteria

Participants meeting any of the following criteria will be eliminated: (1) incorrect enrollment; or (2) poor compliance or voluntary withdrawal.

Participants meeting any of the following criteria will be removeded from the study: (1) experiencing intolerable pain during the study that can not be alleviated by medication; or (2) experiencing serious adverse events (AEs) or complications during the study period.

Randomization and Allocation

The trial uses SPSS V.28.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) software to assign numbers 1–138 to all participants, allocating them to two groups in a 1:1 ratio through a random number generator. A third party not involved in the trial generates and stores the random numbers. Grouping information is placed in opaque envelopes and, when participants are included they are randomly assigned to different groups to receive specific interventions.

Blinding and Unblinding

Given the specific nature of acupuncture manipulation, achieving double blinding is challenging, so participants are only blinded using non-penetrating sham needling.17,18 At the end of the treatment, participants will be asked to guess whether they have received genuine acupuncture. Meanwhile, care providers, data collectors, and data analysts are unclear about the groupings and interventions. Typically, unblinding occurs following data analysis but may be done earlier to ensure participant safety under certain necessary circumstances, such as severe AEs. Emergencies are first treated by the acupuncturist in conjunction with the professional staff, trying to maintain blinding from other researchers. Details are reported on the appropriate case report form (CRF) page.

Interventions

All participants will receive two routine treatments: local hot compress and massage. Licensed acupuncturists with at least 3 years of experience carry out acupuncture treatments for both groups. Acupuncturists are trained in advance on standardized practices. Acupuncture interventions are initiated on the first postpartum day following the initial oxytocin administration and continued for three consecutive days. Considering the painful characteristics of contractions, to enhance the analgesic effect, the treatment is performed twice a day, more than 6 hours apart, for 30 minutes each time, and stimulation occurs at 15 minutes.19,20

Observation Group

Treatment is performed using conventional acupuncture (Figure 2A). Based on Chinese medicine meridian theory, long-term clinical experience and references, bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Diji (SP8), Taichong (LR3), and Zulinqi (GB41) are selected,21–24 and follow World Health Organization localization criteria25 (Figure 3 and Table 2). The acupuncturist uses 0.30×40 mm Huatuo brand disposable acupuncture needles (Suzhou Medical Supplies Factory Limited, license number: Su Food and Drug Administration of Machinery Production 20010020; registration certificate number: 201622770970) and the Park Sham Acupuncture Devices (PSDs). The PSD (Figure 2) includes a transparent catheter (Φ 4×20 mm), two opaque bases (Φ 4×15 mm, Φ 5×10 mm), and double-sided foam tape (Φ 1×15 mm) (produced by Suzhou Medical Supplies Factory, China, batch number: 210401). The acupuncturist assists the participant in a comfortable supine position, exposed the skin below both knees and sterilizes the acupuncture site with 75% alcohol. The needles are placed into PSDs, exposing the tip, and the needle is secured at the acupuncture point with the help of foam tape. Vertical puncture occurs at SP36 and SP8 to 10–15 mm, LR3, and at GB4 to 15–10 mm (depth adjusted to patient muscle thickness). For each acupoint, lifting, inserting, and rotating movements of the needle to stimulate the De-qi sensation are gently performed, and maneuvers are repeated after 15 minutes. Women are kept warm during interventions. After 30 minutes, the acupuncturist removes the acupuncture needles and PSDs and, lightly presses the skin with a sterile dry cotton ball for a few seconds.

|

Table 2 Location of Acupoints |

|

Figure 3 Acupoints selected in this study. |

Control Group

The control group uses the exact specifications of sterile blunt-tipped needles (Suzhou Medical Supplies Factory, lot number: 9018390000, China) and PSDs for non-insertion interventions at the same acupoints (Figure 2B). The acupuncturist fixes blunt needles at the acupuncture points and slowly lifts, inserts and rotates them vertically downward, with the needles forming a depression with the plane of the skin but not piercing it. Participants will experience a pinprick sensation during this process, at which point the needle will be returned to the foam tape. The process is repeated after 15 minutes. Other operations are the same as those performed in the observation group.

Remedial Measures

When a participant needs analgesia, diclofenac sodium suppositories (Hubei Tongshun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd) will be provided if the participant’s UCPCS lasts >30 minutes in a single session, or ≤30 minutes but occurring at a frequency of ≤30 minutes per session and with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score of ≥4.26 This is because the duration of UCPCS varies from a few seconds to several hours per episode, and the onset time of diclofenac sodium suppositories is approximately 30 minutes. It is also used to treat other types of pain with a VAS ≥4. The kind of pain, VAS score, and time to remission are recorded in detail on the pain record sheet (Supplementary Material 3) and the CRF.

Follow-Up

In general, UCPCS disappeared around 7 days after delivery. However, Zheng’s study showed that the average duration of UCPCS was 16.48 days.27 That study was the longest we could find on the duration of uterine contraction pain and, bearing its results in mind, we set our study period at 17 days, with 2-week follow-up post-acupuncture treatment to fully observe UCPCS.

Outcomes and Assessment

Primary Outcome

Mean UCPCS degree at different time points: the assessment uses a 10 cm VAS, where 0–10 indicated no pain to the most severe pain (Supplementary Material 3).

Secondary Outcomes

These outcomes are closely related to UCPCS. First, the intensity, frequency, duration, and number of days until disappearance of UCPCS are recorded in detail using the pain record sheet (Supplementary Material 3), completed each time pain occurs, and averages when analyzing data. Second, the amount of vaginal bleeding and lactation are measured at different time points using the weighing method and lactation score (Supplementary Material 4).28,29 Time of first breastfeeding is also recorded. Meanwhile, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score is used to assess the impact of UCPCS on participants’ mood.30 The EPDS has a total score of 30, with a score of more than 13 suggesting a risk of postpartum depression and higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Finally, the use of analgesic medication is documented.

Other Secondary Outcomes

Before the intervention, acupuncture treatment expectation levels are quantified using a 4-point scale (0=none; 1=1–30%; 2=31–70%; and 3=71–100% improvement). Following the intervention, the following are recorded: first time of exhaustion, frequency of urination and defecation, blinding, treatment satisfaction, adherence, and AEs.

Sample Size

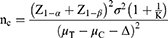

This study hypothesizes that the observation group will be more effective than the control group in treating UCPCS, with a minimum clinically significant difference of 1.6 cm based on VAS score.31 One study showed that, after 2 days of UCPCS treatment, the acupuncture group experienced a change in VAS scores of 5.28±0.6, while the control group showed a shift of 2.24±0.63.14 Considering the pain characteristics, we predict a VAS score reduction of 5.28±0.6 in the observation group and 3.33±0.6 in the control group after 3 days of treatment; that is, α=0.025, β=0.1, Δ=1.6, K=1, according to the formula:32

This trial requires 62 participants per group, with a 10% dropout rate, totaling 69. In total, 138 participants are planned.

Data Collection, Management, and Quality Control

Demographic data are collected from the e-case system, and data collectors gather other data through direct interaction with participants via different means (see Outcomes section). Both paper and online CRF will be used to manage data efficiently. One researcher records raw data promptly, using the paper CRF, and two cross-enter data into the online CRF. Finally, two statistical analysts analyze the data. Participants’ data will be retained for 5 years after completion of the study.

To control data quality and ensure rigor and consistency, rigorous training of the personnel involved in the study (including acupuncturists, nursing operations, data collectors, entrants, analysts, etc) was carried out before recruiting participants. All personnel are required to work strictly according to the study protocol. Data collectors are immediately contacted for verification if data anomalies or missing information are found during entry. Analysts process the data promptly and report any issues to the collectors. Any changes to the paper CRF are noted next to the original data, including the person responsible, date, reason, and modified data. The study leader and the ethics committee regularly review the data collection and processing procedures.

Statistical Methods

All data will be processed and analyzed using SPSS software. Variables conforming to a normal distribution will be expressed as mean±standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables will be presented as median and interquartile range. Normality will be assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test (P>0.05). Ordinal variables and count variables will be expressed using percentages. Paired-sample t-tests will be used when variables conform to a normal distribution and the variances are congruent, and Welch’s t-tests will be used when the variances are not congruent. If neither is satisfied, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test will be used. Nonparametric tests will be applied for categorical variables. Ordinal variables will be analyzed using either chi-square tests or rank sum tests. The data from multiple observation time points will be analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM), depending on the data’s distribution. P<0.05 is considered a statistically significant difference. The study will adhere to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle and employ multiple imputations for handling missing data.

Adverse Events

Adverse events in this study are defined as a participant experiencing any adverse medical event. Collection of AE data begins after participant enrollment. If AEs occur before treatment, they are not related to the intervention. All AEs throughout the study will be recorded and detailed on the CRF. These AEs may include acupuncture-related events such as prolonged pain at the needle site, ecchymosis, hematoma, infection, etc., or drowsiness, dysuria, nausea, and vomiting due to NSAIDs. If AEs occur, they will be treated promptly by a medical professional. If the criteria for serious AEs are met, they will be reported to the ethics committee as serious AEs.

Confidentiality

This trial assigns numbers to conceal the true identities of participants. Any information about the participant is kept strictly confidential and will not be disclosed without authorization to any individual or organization other than the involved physician. Only data entry and analysis personnel have access to the CRF, and the final publicized results of the study will not include any personal information relating to participants. Participants’ medical records are stored at the hospital, and access is granted to researchers and the ethics committee only if they have signed an informed consent form.

Protocol Modification

The study protocol, informed consent form, recruitment materials, and other documents will be approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The ethical review body will review and approve any subsequent modifications, including changes in study objectives, study design, patient population, sample size, study procedures, etc.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although UCPCS is a normal physiological phenomenon, it will disappear naturally after a few days. However, during early puerperium, women experience severe UCPCS, which has become one of their main complaints.14,33 Therefore, early puerperal analgesic intervention in UCPCS is critical. Considering drug safety issues, this study uses acupuncture as an intervention, which is a safe and effective non-pharmacologic analgesic therapy.

After cesarean section, uterine contraction returns to the normal physiological state. The muscle layer compresses sensory nerve endings, releasing neurotransmitters, and compresses blood vessels, releasing inflammatory mediators that generate pain. Vascular compression leads to ischemia-reperfusion injury, causing uterine muscle contraction and worsening pain. The increased sensitivity to pain and the stimulation of endogenous oxytocin are also vital pathways contributing to uterine contraction pain.34 Acupuncture exerts its analgesic effect by modulating multiple systems to reduce pain sensitivity, inhibit inflammation, and improve blood circulation.13,35,36 Based on Chinese medicine meridian theory and long-term clinical experience, this study selected eight acupoints from the spleen, stomach, liver, and gallbladder meridian for intervention. The spleen and stomach meridians are commonly used in treating postpartum uterine contraction pain; the liver meridian regulates qi and blood flow to relieve pain; and the gallbladder meridian connects to the belt vessel, the pathway of which traverses the uterine region. Additionally, the analgesic effects of the selected acupoints have been validated in some studies.21–24 Since uterine contraction pain is most intense during the first three days postpartum, this study administers acupuncture treatment for three days, twice a day, for 30 minutes each time, at six-hour intervals, aiming to achieve better therapeutic effects.19,20

The main objective of this study is to validate the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in treating UCPCS. Therefore, we use the reliable and widely used VAS to measure the UCPCS degree.33 Pain intensity, frequency, duration, and number of days before disappearance of pain are also recorded in detail. Since uterine contractions are closely related to vaginal bleeding and lactation, measuring the amount of vaginal bleeding and lactation can indirectly reflect UCPCS.4,5 Both are calculated using weighed and lactation scores to ensure data accuracy and objectivity.28,29 Previous studies have shown that severe postpartum pain increases the risk of depression, so the EPDS is used to assess the effect of UCPCS on maternal mood.37

In contrast to previous studies of acupuncture for UCPCS, the present study is the first to use non-penetrating sham acupuncture as a control.17 It is similar in appearance to regular acupuncture and is carried out with a needling sensation but does not penetrate the skin. This is advantageous in achieving participant blindness and reducing the placebo effect. However, this study also has some limitations. First, it is single-center, limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, acupuncturists must control the needling technique, making it challenging for blind acupuncturists. Third, this study only focuses on uterine contraction pain, excluding other pain types. Finally, the study is limited by a lack of biochemical assays to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of acupuncture-induced analgesia.

In conclusion, this study’s results are expected to provide an effective therapeutic option for UCPCS and strong evidence for clinicians and researchers who use non-pharmacological interventions.

Abbreviations

UCPCS, uterine contraction pain post-cesarean section; RCT, randomized control trial; VAS, visual analogue scale; EPDS, edinburgh postnatal depression scale; ITT, intention-to-treat; AEs, adverse events; CRF, case report form; PSD, park sham acupuncture device; ANOVA, repeated measures analysis of variance; GLMM, generalized linear mixed model.

Data Sharing Statement

The data produced in this trial will be available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request after successful publication.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The ethical specifications for the study protocol and informed consent materials were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ludian County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (LD2024-002) on 6 May 2024. All participants will be informed about the study in detail and will provide written informed consent before formal enrollment; they can withdraw from the study at any time.

Trial Status

The first participant was successfully enrolled on July 1, 2024. Participant recruitment is expected to conclude by January 2026, with study completion projected for April 2026.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to all the investigators, clinical staff, and participants involved in the trial.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study is supported by the Yunnan High-level Talents in Traditional Chinese Medicine Discipline Leader (Chinese Medicine Acupuncture): Guo Taipin, the “Liang Fanrong Expert Workstation” of Yunnan Province-Yunnan Science and Technology Programme (202305AF150072), the Yunnan Ten Thousand Talents Plan Youth Project (YNWR-QNBJ-2019-257) and the “Liu Zili Famous Doctor” special talent program of the Yunnan Provincial Xing Dian Talent Support Program (Yunnan Party Talent Office 2022 No. 18). These funding sources had no role in the design of this study, in its execution, analysis, or interpretation, and will not determine the submission of results.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6):e005671. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005671

2. Chen L, Shi HF, Wei Y, et al. Analysis of the report on medical service and quality safety of obstetrics in China in 2019. Chin Health Qual Manag. 2022;29(05):1–5+16+8. doi:10.13912/j.cnki.chqm.2022.29.05.01

3. Mo X, Zhao T, Chen J, et al. Programmed intermittent epidural bolus in comparison with continuous epidural infusion for uterine contraction pain relief after cesarean section: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2022;16:999–1009. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S350418

4. Abedi P, Jahanfar S, Namvar F, et al. Breastfeeding or nipple stimulation for reducing postpartum haemorrhage in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(1):CD010845. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010845

5. No GT. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017;124(5):e106–e149. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14178

6. Komatsu R, Ando K, Flood PD. Factors associated with persistent pain after childbirth: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124(3):e117–e130. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.037

7. Gadsden J, Hart S, Santos AC. Post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5 Suppl):S62–S69. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000177100.08599.C8

8. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstetrics Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e35–e43. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002683

9. Macones GA, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations (part 3). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):247.e1–247.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.012

10. Mkontwana N, Novikova N. Oral analgesia for relieving post-caesarean pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(3):CD010450. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010450.pub2

11. Vosoughin M, Mohammadi S, Dabbagh A. Intravenous ketamine compared with diclofenac suppository in suppressing acute postoperative pain in women undergoing gynecologic laparoscopy. J Anesth. 2012;26(5):732–737. doi:10.1007/s00540-012-1399-1

12. Zhang M, Shi L, Deng S, et al. Effective oriental magic for analgesia: acupuncture. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:1451342. doi:10.1155/2022/1451342

13. Zhu X, Jia Z, Zhou Y, et al. Current advances in the pain treatment and mechanisms of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Phytother Res. 2024;38(8):4114–4139. doi:10.1002/ptr.8259

14. Xu CB. Clinical study on acupuncture at Sanyinjiao and Yinlingquan acupoints for the treatment of afterpains of cesarean section. Int Med Health Guid News. 2020;26(1):58–60. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-1245.2020.01.017

15. Song M. Progress on the treatment of afterpains with traditional Chinese medicine. Guangxi J Tradit Chin Med. 2024;47(01):69–73.

16. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7586

17. Park J, White A, Stevinson C, et al. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(4):168–174. doi:10.1136/aim.20.4.168

18. Lee H, Bang H, Kim Y, et al. Non-penetrating sham needle, is it an adequate sham control in acupuncture research? Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S41–8. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.002

19. Bian JL, Zhang CH. Conception and core of academician Shi Xuemin’s acupuncture manipulation quantitative arts. Chin Acupun & Mox. 2003;23(05):38–40.

20. Yang XG, Li XZ, Fu NN, et al. Effect of acupuncture for pain threshold among the groups of different constitutions. Chin Acupun & Mox. 2016;36(05):491–495. doi:10.13703/j.0255-2930.2016.05.011

21. Jin Y, Yu X, Hu S, et al. Efficacy of electroacupuncture combined with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(2):100826. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100826

22. Gharloghi S, Torkzahrani S, Akbarzadeh AR, et al. The effects of acupressure on severity of primary dysmenorrhea. Patient Prefer Adher. 2012;6:137–142. doi:10.2147/PPA.S27127

23. Xisheng F, Xiaoyi DU, Lijia P, et al. An infrared thermographic analysis of the sensitization acupoints of women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Tradit Chin Med. 2022;42(5):825–832. doi:10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.20220707.004

24. Li TL, Zhan YR, Liu XN, et al. On the rule of acupuncture and moxibustion in ancient books of Traditional Chinese Medicine for the treatment of pain related to menstrual disease. Tradit Chin Med J. 2023;22(07):37–40+50. doi:10.14046/j.cnki.zyytb2002.2023.07.003

25. Pacific WROft W. WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations in the Western Pacific Region. Manila: World Health Organization; 2008.

26. Zhou SF, Wang HY, Wang K. An analysis of the surgical outcomes of laparoendoscopic single-site myomectomy and multi-port laparoscopic myomectomy. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(11):927. doi:10.21037/atm-21-1862

27. Zheng LL. Effect of self-formulated uterine resuscitation soup on uterine resuscitation insufficiency after cesarean delivery. Chinese J Trad Med Sci Tech. 2022;29(05):824–826.

28. Kerr R, Eckert LO, Winikoff B, et al. Postpartum haemorrhage: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2016;34(49):6102–6109. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.039

29. Zhang RY, Zhang XR, Guo CF, et al. Clinical random trial of thumbtack needling therapy for analgesia after cesarean section. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2022;47(8):719–723. doi:10.13702/j.1000-0607.20210959

30. Levis B, Negeri Z, Sun Y, et al. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2020;371:m4022. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4022

31. Gallagher EJ, Bijur PE, Latimer C, et al. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(4):287–290. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.33778

32. Hu J, Li B, Zhang HN, et al. Sample size estimation in acupuncture and moxibustion clinical trials. Chin Acupun & Mox. 2021;41(10):1147–1152. doi:10.13703/j.0255-2930.20201020-0002

33. Eshkevari L, Trout KK, Damore J. Management of postpartum pain. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(6):622–631. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12129

34. Li CL, Cai J, Cui JZ. Research progress on the mechanism of postpartum uterine contraction pain and its analgesic treatment. J Qiqihar Med Univ. 2023;44(07):671–677.

35. Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85(4):355–375. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.05.004

36. Chen T, Zhang WW, Chu YX, et al. Acupuncture for pain management: molecular mechanisms of action. Am J Chin Med. 2020;48(4):793–811. doi:10.1142/S0192415X20500408

37. Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140(1):87–94. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.011

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Acupuncture for Pain and Function in Patients with Nonspecific Low Back Pain: Study Protocol for an Up-to-Date Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Li Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhai M, Li L, Yuan S, Li Y

Journal of Pain Research 2022, 15:1379-1387

Published Date: 10 May 2022

Effect of Acupuncture on the Cognitive Control Network of Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial

Yin S, Zhang ZH, Chang YN, Huang J, Wu ML, Li Q, Qiu JQ, Feng XD, Wu N

Journal of Pain Research 2022, 15:1443-1455

Published Date: 18 May 2022

The Efficacy and Safety of Acupuncture for Depression-Related Insomnia: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Hu H, Li Z, Cheng Y, Gao H

Journal of Pain Research 2022, 15:1939-1947

Published Date: 13 July 2022

The Effectiveness of Pharmacopuncture in Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Protocol for a Multi-Centered, Pragmatic, Randomized, Controlled, Parallel Group Study

Lee JY, Park KS, Kim S, Seo JY, Cho HW, Nam D, Park Y, Kim EJ, Lee YJ, Ha IH

Journal of Pain Research 2022, 15:2989-2996

Published Date: 23 September 2022

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol on How Best to Use Non-Pharmacologic Therapies to Manage Chronic Low Back Pain and Associated Depression

Guo Y, Ma Q, Zhou X, Yang J, He K, Shen L, Zhao C, Chen Z, Tan CIC, Chen J

Journal of Pain Research 2022, 15:3509-3521

Published Date: 4 November 2022