Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 18

High Pain Self-Efficacy Reduces the Use of Analgesics in the Early Postoperative Period After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Authors Sonobe T , Nikaido T , Sekiguchi M, Kaneuchi Y , Kikuchi T , Matsumoto Y

Received 12 December 2024

Accepted for publication 12 March 2025

Published 19 March 2025 Volume 2025:18 Pages 1407—1415

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S511719

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Alaa Abd-Elsayed

Tatsuru Sonobe,1 Takuya Nikaido,1 Miho Sekiguchi,1 Yoichi Kaneuchi,1 Tadashi Kikuchi,2 Yoshihiro Matsumoto1

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine, Fukushima, Japan; 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Bange-Kosei General Hospital, Fukushima, Japan

Correspondence: Takuya Nikaido, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine, 1 hikarigaoka, Fukushima-shi, Fukushima, 960-1295, Japan, Tel +81-24-547-1276, Fax +81-24-548-5505, Email [email protected]

Background: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an effective treatment for relieving pain and restoring physical function in individuals with severe knee osteoarthritis (KOA). However, the persistence of postoperative pain is an unresolved problem, and the use of postoperative analgesics to deal with this pain is increasing. The positive cognitive factor known as pain self-efficacy (PSE) has been shown to moderate the intensity of pain, but there are few reports of PSE concerning analgesic use after TKA. We sought to clarify the effect of PSE on postoperative analgesic use in TKA cases.

Patients and Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 60 patients who underwent bilateral TKA surgery for bilateral severe KOA. A multiple linear regression model including covariates and scaling estimation coefficients was used to investigate the effect of PSE on the patients’ postoperative analgesic use. We identified the presence/absence of postoperative analgesic use at 3 and 6 months postoperatively, and other evaluation items such as the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) were evaluated at the time of the patients’ admission for surgery.

Results: In a multiple linear regression model, only high PSE had a significant impact on the postoperative 3-month use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (β: − 0.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]: − 0.51, − 0.01). However, the significant difference had disappeared postoperative 6 months (β: − 0.06, 95% CI: − 0.19, 0.31).

Conclusion: These results demonstrated that high pain self-efficacy reduced the analgesic use at 3 months postoperatively by patients who have undergone bilateral TKA surgery, but it did not affect analgesic use at 6 months postoperatively. Pain self-efficacy can be an intervention target for reducing the use of analgesics after TKA surgery. Further research is needed to clarify the relationship between pain self-efficacy and the post-TKA use of analgesics.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, self-efficacy, total knee arthroplasty, analgesics

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), one of the most common surgical procedures,1,2 is considered an effective procedure for relieving pain and restoring physical function in individuals with severe knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Bilateral TKA is a safe and cost-effective treatment, and comparable postoperative outcomes have been reported compared to unilateral TKA.3 However, compared to unilateral TKA, simultaneous bilateral TKA is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, acute hemorrhagic anemia, and blood transfusion.4 Therefore, more investigators believed that staged bilateral TKA is a safer approach than simultaneous bilateral TKA.5 In staged bilateral TKA, a previous study reported that patients experience more severe postoperative pain within 48 hours of the second knee surgery than after the first knee surgery,6 and the importance of postoperative pain management is attracting attention.

Postoperative pain is the most common complaint of patients after surgery.7 Postoperative pain is also one of the important factors affecting the patient’s postoperative knee function.6 Although there has been extensive in-depth research on perioperative analgesia for TKA, including preventative analgesia, intraoperative infusion of analgesic cocktails, and multimodal analgesia, the problem remains unresolved. In particular, 13%–44% of knees that have undergone an arthroplasty develop chronic pain after surgery.8 The use of analgesics, including opioids, to treat postoperative pain has increased over the past decade.8 In the US, deaths from prescription opioids have increased by more than fourfold since 1999, and this trend is now being seen worldwide.8 The long-term use of opioids after TKA is also a problem, and it is particularly necessary to reduce the long-term use of analgesics by patients who are at high risk of abusing these drugs.9

Pain self-efficacy (PSE) is a positive cognitive factor that is considered a protective factor contributing to adaptation despite pain,10,11 and PSE has been shown to moderate the relationship between pain intensity and physical disability.12,13 Among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), those with low PSE have been reported to use analgesics more frequently and complain of more intense pain.14 PSE is also a significant predictor of functional ability after TKAs performed for KOA.15 However, our search of the relevant literature identified only a few studies of the impact of PSE on post-TKA pain. In abdominal surgery, PSE is negatively correlated with acute postoperative pain.16 In other words, patients with high PSE tend to experience less postoperative pain.16 Similarly, in TKA surgery, PSE may also be related to postoperative pain, which affects the long-term use of analgesics. Clarifying the impact of PSE on analgesic use after TKA conducted for patients with severe KOA will be useful for the selection of treatment strategies for pain management after TKA, and it may contribute to the optimization of analgesic use. We conducted this study to determine the effects of PSE on analgesic use by patients who have undergone a TKA.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This was a retrospective cohort study of 60 patients who underwent bilateral TKA surgery for bilateral KOA at Bange-Kosei General Hospital (Fukushima, Japan) during the period from December 2022 through November 2023. All of the patients with Kellgren-Lawrence grade17 (KL grade) III or IV KOA in both knees and who underwent bilateral TKA surgeries during the inclusion period were enrolled, without age restriction (Figure 1). All surgeries were performed one side at a time, with the contralateral side performed 14 days after the unilateral surgery. All patients underwent the same surgical protocol, and the implants used were consistent. The postoperative rehabilitation protocols were also consistent among the all patients. The patients of this study began full-weight bearing walking and unrestricted range of motion training under the guidance of a physiotherapist from the day after surgery. The daily rehabilitation time was 30 minutes, and it was carried out every day until discharge, excluding the day of surgery on the contralateral side. We excluded patients with a history of previous knee surgery, trauma, or RA (rheumatoid arthritis). Patients with cognitive decline who were unable to complete the study questionnaire were also excluded.

Antibiotics/Thromboprophylaxis Protocols

All patients administrated prophylactic antibiotics within 30 minutes before surgery. After surgery, prophylactic administration was continued every 6 hours, and the administration was terminated 24 hours after surgery. In all cases, first-generation cephalosporins were used as prophylactic antibiotics. To prevent thrombosis, all patients wore elastic stockings before and for 10 days after surgery. Lower extremity venous ultrasonography was performed on the second day after surgery, and if a thrombosis was found proximal to the popliteal vein, edoxaban was administered for 5 days. On the 7th day after surgery, the ultrasonography was rechecked, and if the thrombosis had reduced in size and length, edoxaban administration was terminated. However, it had not changed, edoxaban was administered for an additional 7 days.

Postoperative Pain Control

For each patient, the postoperative pain management was comprised of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) only. Patients who were unable to use NSAIDs due to side effects or other reasons and patients who had been using other analgesics were excluded from the study. Cases in which NSAIDs were used for reasons other than postoperative knee pain were also excluded. At 3 and 6 months after each bilateral TKA, the patients were assessed for the use of NSAIDs, regardless of the NSAID amount.

Data Collection

We obtained the patients’ demographics from their medical records, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and complications such as diabetes mellitus (DM). Referring to the age at the time of admission, we divided into three categories: <65, 65–74, and ≥75. BMI was also divided into two groups: <25 and ≥25. The presence or absence of DM was determined by examining the patient’s current medical history and classifying them into two groups.

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ)

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a 10-item self-reported questionnaire designed to evaluate the degree of confidence in one’s ability to perform a variety of activities despite experiencing pain.18 Each item of the PSEQ is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = not confident at all, 6 = completely confident). The total PSEQ score ranges from 0 to 60 points, with higher scores indicating greater PSE to perform activities even in the presence of pain. The Japanese version of the PSEQ has been verified, and its validity has been confirmed.19 The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the PSEQ was 0.92 for the original version and 0.94 for the Japanese version, indicating a high level of reliability.18,19

The PSEQ used in the present study was shown to be reliable based on a systematic review of PSE measures.20 As in other reports,18,20 we classified the present 60 patients with a PSEQ score <40 points as the normal-PSE group (N group) and the patients with a score ≥40 points as the high-PSE group (H group).

The Brief Scale for Psychiatric Problems in Orthopaedic Patients (BS-POP)

Psychiatric problems such as anxiety and depression are associated with postoperative pain in patients who have undergone a TKA.21 The Brief Scale for Psychiatric Problems in Orthopaedic Patients (BS-POP) is a questionnaire used to assess psychiatric problems in clinical practice,22 with two components: one for physicians and one for patients. The physician component consists of eight questions, with the physician answering each question based on the patient’s assessment. Each question is rated on a 3-point scale, with total scores ranging from 8 to 24 points, with higher scores indicating more problems. The patient component of the BS-POP consists of 10 questions, which the patient completes to assess mood problems. Each item is rated on the same scale as the physician component, with total scores ranging from 10 to 30 points, with higher scores indicating more severe psychiatric problems. In the present study, we defined a score ≥11 points on the physician component or a combination of ≥10 points on the physician component and ≥15 points on the patient component as an abnormal BS-POP result; lower scores were defined as a normal BS-POP result.22

Knee Conditions

Each patient completed the validated version of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)23 for both knees. The results reflected the condition of the knee on the worse side. The KOOS is composed of five subscales (symptoms, pain, activities of daily living [ADLs], sports and recreation, and quality of life [QOL]), and each subscale is independently rated as 0–100 points (0 = severe knee problems, 100 = no problems). Each patient’s pre-operative KOOS was measured at the time of their admission, and their postoperative KOOS score was evaluated at 3 and 6 months after the bilateral TKA. Since most patients are not usually engaging in the activities measured by the KOOS’ sports and recreation subscale (such as running and jumping), we considered that this subscale would be of little significance in evaluating the results of TKA surgery, and we thus examined the KOOS sports and recreation subscale in this study but did not analyze its results.

Ethical Consideration

Written informed consent for the use of the data collected in this study was obtained from all patients upon enrollment. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Fukushima Medical University (No. 2022–175).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the patients’ baseline characteristics. Continuous data are summarized as the mean and standard deviation, and dichotomous or categorical data are presented as proportions. We used the Shapiro–Wilk test to check the normality of the variables. The normality of all variables was not rejected, with p≥0.05. Comparative analyses of each factor in the N and H groups were performed using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. We examined the association between the postoperative use of NSAIDs and the PSEQ score by applying a multiple linear regression model which included covariates (age, sex, BMI, DM, BS-POP) and scaled estimated regression coefficients (β). The variance inflation factor (VIF) is a measure of multicollinearity in a set of multiple regression variables, and a high VIF indicates that the associated independent variable is highly collinear with other variables in the model. Probability (p)-values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using JMP PRO 16 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

The characteristics of the 60 patients are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, DM, or BS-POP between the N (n=38) and H groups (n=22). The pre- and postoperative 3-month KOOS pain scores were significantly higher in the H group compared to the N group (p=0.0403 and p=0.0380, respectively), indicating that the severity of pain was lower in the H group compared to the N group both before and 3 months after the TKA surgery. No significant differences were shown in the other KOOS subscales.

|

Table 1 The Participants’ Characteristics |

Factors That Influenced the Postoperative 3-month Use of NSAIDs in the Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

High PSE had a negative effect on the patients’ postoperative 3-month use of NSAIDs (β: −0.30, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.55, −0.04), whereas age, sex, BMI, DM, and BS-POP did not significantly influence the postoperative 3-month use of NSAIDs (Table 2). As the VIF of each covariate was quite low in this analysis, there was no multicollinearity between the covariates.

|

Table 2 Influence Factors of Post-Operative 3-month Use of NSAIDs in the Multiple Linear Regression Analysis |

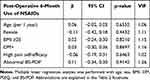

Factors That Influenced the Postoperative 6-month Use of NSAIDs in the Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

The patient age, sex, BMI, DM, PSEQ score, and BS-POP score did not significantly influence the patients’ 6-month use of NSAIDs (Table 3). At postoperative 3 months, High PSE had a significant negative impact on the use of NSAIDs, but this significant difference disappeared postoperative 6 months. There was no multicollinearity between the covariates, as the VIF of each covariate was quite low in this analysis.

|

Table 3 Influence Factors of Post-Operative 6-month Use of NSAIDs in the Multiple Linear Regression Analysis |

Discussion

Our findings revealed that high PSE reduced the use of NSAIDs at 3 months after bilateral TKA surgery for severe bilateral KOA, but it did not affect postoperative the 6-month use of NSAIDs by the same patients. This study appears to be the first to analyze the impact of PSE on postoperative analgesic use in patients with bilateral severe osteoarthritis of the knees who have undergone bilateral TKA surgery. Our results corroborate and extend the findings of previous studies.

The results of our analyses demonstrated that the pre- and postoperative 3-month knee pain was significantly lower in the H group compared to the N group. Pre-TKA pain is pain originating from KOA, such as progressive articular cartilage degeneration24 and synovitis.25 Early post-TKA pain includes the pain associated with surgical invasion,26 a limited range of motion due to fibrous scarring,27 and edema.28 In particular, tissue damage caused by surgical invasion leads to local and systemic inflammatory conditions.29 This is a physiological response in the wound healing process. Within hours after surgery, damage response antigens and alarm factors rapidly accumulate, activating neutrophils and monocytes.30 This initial “rolling” process of white blood cells (WBC) is accompanied by platelet (PLT) adhesion, leading to the exudation of WBC to the site of inflammation or infection.31 The administration of NSAIDs in the early postoperative period is effective for improving inflammatory conditions associated with physiological reactions. However, long-term use of NSAIDs can cause various side effects, so they should be avoided. The long-term use of NSAIDs has been shown to increase the risk of peptic ulcer,32 upper gastrointestinal bleeding,32 and upper gastrointestinal perforation.33 In patients >65 years old, an inappropriate use of NSAIDs more than doubles the risk of acute kidney injury.34 The side effects of long-term NSAID use are wide-ranging. For individuals >65 years old (among whom a TKA is frequently performed), the above-mentioned side effects are fatal and must be avoided. Our present findings are also significant in that they identified factors that lead to a reduction in the use of analgesics in order to avoid serious side effects from NSAIDs.

High PSE is advantageous for pain management,35 and in the present study, the knee pain of the patients with high PSE before and at 3 months after surgery was lower than that in the N group, indicating that high PSE contributes to the reduction of knee pain during this period. However, the postoperative 6-month knee pain was not significantly different between the two groups. It has been demonstrated that knee pain takes at least 6 months to improve after TKA,36,37 by 6 months postsurgery, most patients experience only mild pain or no pain at all.38 Our findings demonstrate that sufficient pain relief can be achieved at 6 months after a TKA, regardless of patients’ PSE status. Since reducing knee pain within the first 6 months after a TKA is common, providing pain relief at an early stage, 3 months after a TKA is important.

Factors that increase the use of analgesics after TKA include being young,39 female,35 DM,36 obesity,40 and anxiety/depression.9 We included these factors, which have been described as high-risk factors for analgesic use, in our present analyses. At postoperative 3 months, in contrast to the results of previous studies, only high PSE had a significant effect on our patients’ analgesic use. Individuals with high PSE can use non-pharmacological pain management techniques such as relaxation and cognitive restructuring more effectively compared to those with low or no PSE.41 A high level of PSE also reduces the intensity of pain and the catastrophic sense of pain that is involved in opioid use.16 In a randomized controlled trial that used perioperative pain self-management interventions such as relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, and improving coping strategies, the intervention group showed reduced pain and decreased analgesic use at 3 months postsurgery.42 In addition, a previous review has shown that physiotherapy improves the PSE of patients with non-specific low back pain.43 In the present study, the same rehabilitation program was provided to all patients, but their baseline PSE may have changed after rehabilitation. It is a future issue to verify the impact of rehabilitation programs tailored to individual patients on post-operative pain and PSE. Improving preoperative pain self-efficacy can be a key factor in reducing the use of analgesics after TKA surgery. Further research is required to investigate this issue.

Several study limitations must be addressed. First, because the multivariate results were obtained for a cross-sectional analysis at each time point, a causal relationship could not be determined. Second, we did not investigate the patients’ detailed history of treatment for KOA or the duration of their disease, which might have affected their knee pain. Third, the sample size was small (60 patients). Fourth, we were unable to include a history of tobacco use in the analyses, although this history has been reported as a factor that affects the use of analgesics after TKA surgery.44 Finally, we focused on whether or not analgesics were used and did not consider the amount used.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that a high level of PSE reduced analgesic use at 3 months postoperatively in patients who had undergone bilateral TKA surgery (β: −0.27, 95% CI: −0.51, −0.01). However, it did not affect analgesic use at 6 months postoperatively (β: −0.06, 95% CI: −0.19, 0.31). PSE can be an intervention target for reducing the use of analgesics after TKA surgery. Further research is needed to clarify the relationship between PSE and the use of analgesics after TKA.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Bange-Kosei General Hospital for their help with patient recruitment and data acquisition. We also thank all of the patients who agreed to participate in the study.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

1. Ritter MA, Keating EM, Sueyoshi T, Davis KE, Barrington JW, Emerson RH. Twenty-five-years and greater, results after nonmodular cemented total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2199–2202. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.043

2. Kahlenberg CA, Nwachukwu BU, McLawhorn AS, Cross MB, Cornell CN, Padgett DE. Patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: a systematic review. HSS J. 2018;14(2):192–201. doi:10.1007/s11420-018-9614-8

3. Jiang C, Zhao Y, Feng B, et al. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in patients with end-stage hemophilic arthropathy: a mean follow-up of 6 years. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1608. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19852-7

4. Richardson MK, Liu KC, Mayfield CK, Kistler NM, Christ AB, Heckmann ND. Complications and safety of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a patient characteristic and comorbidity-matched analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023;105(14):1072–1079. doi:10.2106/JBJS.23.00112

5. Hu J, Liu Y, Lv Z, Li X, Qin X, Fan W. Mortality and morbidity associated with simultaneous bilateral or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(9):1291–1298. doi:10.1007/s00402-011-1287-4

6. Sun J, Li L, Yuan S, Zhou Y. Analysis of early postoperative pain in the first and second knee in staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective controlled study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129973

7. Cross WW, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, Kane RL. Agreement about indications for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:34–39. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000214436.49527.5e

8. Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS. Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1537–1546. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30352-6

9. Ward R, Taber D, Gonzales H, et al. Risk factors and trajectories of opioid use following total knee replacement. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2022;34(1):18. doi:10.1186/s43019-022-00148-0

10. Turk DC. A diathesis-stress model of chronic pain and disability following traumatic injury. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(1):9–19. doi:10.1155/2002/252904

11. Woby SR, Urmston M, Watson PJ. Self-efficacy mediates the relation between pain-related fear and outcome in chronic low back pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(7):711–718. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.10.009

12. Arnstein P, Caudill M, Mandle CL, Norris A, Beasley R. Self efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between pain intensity, disability and depression in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1999;80(3):483–491. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00220-6

13. Miró E, Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Prados G, Medina A. When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(4):799–814. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02016.x

14. Blamey R, Jolly K, Greenfield S, Jobanputra P. Patterns of analgesic use, pain and self-efficacy: a cross-sectional study of patients attending a hospital rheumatology clinic. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):137. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-137

15. Wylde V, Dixon S, Blom AW. The role of preoperative self-efficacy in predicting outcome after total knee replacement. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10(2):110–118. doi:10.1002/msc.1008

16. Wang L, Qin F, Liu H, Lu XH, Zhen L, Li GX. Pain sensitivity and acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: the mediating roles of pain self-efficacy and pain catastrophizing. Pain Manag Nurs. 2024;25(2):e108–e114. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2023.12.001

17. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. doi:10.1136/ard.16.4.494

18. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153–163. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008

19. Adachi T, Nakae A, Maruo T, et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire in Japanese patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(8):1405–1417. doi:10.1111/pme.12446

20. Miles CL, Pincus T, Carnes D, Taylor SJ, Underwood M. Measuring pain self-efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(5):461–470. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318208c8a2

21. Judge A, Arden NK, Cooper C, et al. Predictors of outcomes of total knee replacement surgery. Rheumatology. 2012;51(10):1804–1813. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kes075

22. Yoshida K, Sekiguchi M, Otani K, et al. A validation study of the brief scale for psychiatric problems in orthopaedic patients (BS-POP) for patients with chronic low back pain (verification of reliability, validity, and reproducibility). J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(1):7–13. doi:10.1007/s00776-010-0012-4

23. Nakamura N, Takeuchi R, Saito T, Ishikawa H, Saito T, Goldhahn S. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Japanese knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS). J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(5):516–523. doi:10.1007/s00776-011-0112-9

24. Hinman RS, Bennell KL, Metcalf BR, et al. Balance impairments in individuals with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a comparison with matched controls using clinical tests. Rheumatology. 2002;41(12):1388–1394. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1388

25. Cecchi F, Mannoni A, Molino-Lova R, et al. Epidemiology of Hip and knee pain in a community-based sample of Italian persons aged 65 and older. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(9):1039–1046. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.01.008

26. Pitta M, Esposito CI, Li Z, Lee YY, Wright TM, Padgett DE. Failure after modern total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 18,065 Knees. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(2):407–414. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.041

27. Menetski J, Mistry S, Lu M, et al. Mice overexpressing chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) in astrocytes display enhanced nociceptive responses. Neuroscience. 2007;149(3):706–714. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.08.014

28. Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28(1):1–15. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

29. Moldovan F. Correlation between peripheric blood markers and surgical invasiveness during humeral shaft fracture osteosynthesis in young and middle-aged patients. Diagnostics. 2024;14(11):1112. doi:10.3390/diagnostics14111112

30. Gaudillière B, Fragiadakis GK, Bruggner RV, et al. Clinical recovery from surgery correlates with single-cell immune signatures. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(255):255ra131. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009701

31. Cerletti C, de Gaetano G, Lorenzet R. Platelet - leukocyte interactions: multiple links between inflammation, blood coagulation and vascular risk. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):e2010023. doi:10.4084/mjhid.2010.023

32. Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002;359(9300):14–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07273-2

33. Massó González EL, Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, García Rodríguez LA. Variability among nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1592–1601. doi:10.1002/art.27412

34. Schneider V, Lévesque LE, Zhang B, Hutchinson T, Brophy JM. Association of selective and conventional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs with acute renal failure: a population-based, nested case-control analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):881–889. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj331

35. Ferrari S, Vanti C, Pellizzer M, Dozza L, Monticone M, Pillastrini P. Is there a relationship between self-efficacy, disability, pain and sociodemographic characteristics in chronic low back pain? A multicenter retrospective analysis. Arch Physiother. 2019;9(1):9. doi:10.1186/s40945-019-0061-8

36. Rajamäki TJ, Puolakka PA, Hietaharju A, Moilanen T, Jämsen E. Predictors of the use of analgesic drugs 1 year after joint replacement: a single-center analysis of 13,000 hip and knee replacements. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):89. doi:10.1186/s13075-020-02184-1

37. Pynsent PB, Adams DJ, Disney SP. The Oxford Hip and knee outcome questionnaires for arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(2):241–248. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.87B2.15095

38. Rothwell AG, Hooper GJ, Hobbs A, Frampton CM. An analysis of the Oxford Hip and knee scores and their relationship to early joint revision in the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(3):413–418. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.22913

39. Mekkawy KL, Zhang B, Wenzel A, et al. Mapping the course to recovery: a prospective study on the anatomic distribution of early postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplasty. 2023;5(1):37. doi:10.1186/s42836-023-00194-3

40. Edwards RR, Campbell C, Schreiber KL, et al. Multimodal prediction of pain and functional outcomes 6 months following total knee replacement: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):302. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-05239-3

41. Pester BD, Edwards RR, Martel MO, Gilligan CJ, Meints SM. Mind-body approaches for reducing the need for post-operative opioids: evidence and opportunities. J Clin Anesth Intensive Care. 2022;3(1):1–5. doi:10.46439/anesthesia.3.016

42. Hadlandsmyth K, Conrad M, Steffensmeier KS, et al. Enhancing the biopsychosocial approach to perioperative care: a pilot randomized trial of the perioperative pain self-management (PePS) intervention. Ann Surg. 2022;275(1):e8–e14. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004671

43. Gilanyi YL, Wewege MA, Shah B, et al. Exercise increases pain self-efficacy in adults with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(6):335–342. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11622

44. Cao G, Xiang S, Yang M, et al. Risk factors of opioid use associated with an enhanced-recovery programme after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):1046. doi:10.1186/s12891-021-04937-8

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Public Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding the Use of Over-The-Counter (OTC) Analgesics in Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Sinuraya RK, Wulandari C, Amalia R, Puspitasari IM

Patient Preference and Adherence 2023, 17:2569-2578

Published Date: 17 October 2023