Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 20

Quality of Care and Outcomes of Inpatients with COPD: A Multi-Center Study in China

Authors Wang F , Wang M, Chen X, Song A, Zeng H, Chen J, Wang L, Jiang W, Jiang M, Shi W, Li Y, Zhong H, Chen R, Liang Z

Received 11 December 2024

Accepted for publication 10 May 2025

Published 31 May 2025 Volume 2025:20 Pages 1787—1795

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S510613

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Fengyan Wang,1,* Mingdie Wang,1,* Xiaoyan Chen,2,* Aiqi Song,3,* Hui Zeng,3 Jiawei Chen,3 Lingwei Wang,4 Wanyi Jiang,1 Mei Jiang,1 Weijuan Shi,1 Yuqi Li,1 Heng Zhong,5 Rongchang Chen,1,4,* Zhenyu Liang1,*

1State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease, National Center for Respiratory Medicine, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, 510120, People’s Republic of China; 2Foshan Fourth People’s Hospital, Foshan, 528000, People’s Republic of China; 3Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, 510182, People’s Republic of China; 4Hetao Institute of Guangzhou National Laboratory, Shenzhen, 518000, People’s Republic of China; 5R&D China, AstraZeneca, Shanghai, 200040, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Zhenyu Liang, State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease, National Center for Respiratory Medicine, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, 510120, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 13560157649, Email [email protected] Rongchang Chen, State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease, National Center for Respiratory Medicine, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, 510120, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 13902273260, Email [email protected]

Objective: Hospitalization due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation is linked to worse prognosis and increased healthcare burden, especially in low- and middle-income countries. This study aimed to evaluate the quality of care and outcomes among inpatients with COPD and to identify prognostic factors relate to healthcare quality indicators.

Methods: A multi-center, retrospective longitudinal study was conducted. Patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations between January and December 2017 were randomly sampled from 16 secondary or tertiary public general hospitals in China. Healthcare quality process indicators and clinical outcomes were collected from medical records and patient questionnaires. The median follow-up period was 666 days. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for readmission or death within 30 days after discharge and for one-year mortality.

Results: A total of 891 inpatients with COPD were included. Among them, 14.3% underwent post-bronchodilator spirometry. Documentation of exacerbation history and symptom scores was found in 16.8% and 1.2% of medical records, respectively. Long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) were prescribed at discharge in 30.3% of cases. Verbal counseling was the primary approach to smoking cessation education, rather than the 5A method. The 30-day readmission rate was 7.1%. The average exacerbation rate was 0.94 per patient during the following year, and the one-year mortality rate was 7.2%. Prescription of inhaled LABDs at discharge was significantly associated with a lower risk of readmission or death within 30 days (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29– 0.90, p=0.020). The presence of cardiovascular disease was associated with an increased risk of death within one year (HR 2.34, 95% CI 1.24– 4.41, p=0.002).

Conclusion: The quality of inpatient care for COPD in China showed deficiencies in diagnostics, disease assessment, and patient education. Prescription of inhaled LABDs at discharge was a key quality measure that significantly reduced short-term readmission or mortality, highlighting its importance. Standardized protocols and clinician training are essential to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, quality in health care, long-acting bronchodilators, patient readmission, prognosis

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a chronic lung condition characterized by persistent and usually progressive airflow limitation with increased susceptibility to exacerbations, is a major contributor to global morbidity, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), mortality, and healthcare use.1–3 A modeling study based on the Global Burden of Disease database estimated that the global number of COPD cases among individuals aged 25 years and older will rise by 23% from 2020 to 2050, reaching nearly 600 million by 2050.4 Currently, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear the greatest share of the global COPD burden.1 The largest increase in COPD burden is also projected to occur in LMICs.4 Therefore, it is essential to implement quality control measures in disease management to improve outcomes and reduce healthcare burden, especially in LMICs.

COPD exacerbations are episodes of sudden worsening of respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production, typically linked to increased local and systemic inflammation. Recurrent exacerbations are known to result in high short-term readmission rates and increased mortality following an initial hospitalization for exacerbation.5 These episodes account for over half of the direct healthcare costs related to COPD, particularly those requiring hospital admission.6 Hospitalization offers a key opportunity for healthcare providers to deliver optimal care and patient education, particularly in LMICs where primary healthcare systems often fall short in managing chronic diseases. However, large-scale studies that thoroughly evaluate the quality of care during hospitalization and at discharge, as well as its impact on patient outcomes, remain limited.

Healthcare process quality of COPD involves various aspects, including diagnosis, assessment, treatment and patient education. Previous studies have reported poor adherence of respiratory physicians to guideline-recommended treatments for COPD.7,8 Given the heterogeneity of COPD,9–11 comprehensive assessment is essential to guide effective treatment, as recommended by international guidelines and strategies such as the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).12 This assessment should include evaluation of airflow limitation, symptoms, exacerbation history, and comorbidities. Nonetheless, few studies have examined the adequacy of such comprehensive assessments in clinical settings. In addition, it remains unclear whether guideline-recommended inhaled therapies for long-term management are appropriately and sufficiently used in real-world practice, especially in LMICs where access to affordable medications may be limited.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the overall medical care for inpatients with COPD in China and to identify the prognostic factors associated with healthcare quality indicators. The results aim to inform the development of practical and effective strategies for quality control in COPD care.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multi-center, retrospective longitudinal study, conducted as the baseline survey of the QC-COPD trial in China (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03604146). The study included patients managed by their clinicians for COPD exacerbation. Sixteen secondary or tertiary hospitals were randomly selected from public general hospitals in Guangdong Province, China. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No. 201722). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Population

In 2018, 1,000 patients aged over 40 years were randomly selected from 4,766 patients admitted to participating hospitals for COPD exacerbations between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017. A total of 891 patients were included in the analysis after excluding those who did not meet the inclusion criteria or were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Chronic respiratory diseases other than COPD, including lung cancer, active pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and severe bronchiectasis; (2) History of lung surgery; (3) Recently diagnosed malignant tumors; (4) Severe renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >451 µmol/L); (5) Severe hepatic insufficiency (ALT or AST ≥3 times the upper limit of normal); (6) Enrollment in double-blind trial.

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of participant selection. Abbreviation: AECOPD, Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. |

Survey of Medical Quality for COPD

Patients were followed until August 2019, with a median follow-up duration of 666 days. Baseline process quality indicators—including diagnosis, assessment, treatment, and education—as well as outcome quality indicators—such as readmission, acute exacerbation after discharge, and death—were evaluated. Data were collected through the hospital information system (HIS), laboratory information system (LIS), and picture archiving and communication system (PACS). The following information was obtained for medical record review: (1) Demographic characteristics and smoking history; (2) Key healthcare quality indicators, including lung function test completion, smoking cessation education, inhaled medication prescriptions, discharge prescriptions (medications within one month after discharge), and inhalation device education; (3) Disease assessment data, including symptom scores and lung function classification; (4) Utilization of medical resources, such as ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and length of hospital stay; (5) Prognosis information, including the number and date of readmissions. Information on the number and date of post-discharge exacerbations and the date of death was obtained through patient questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Missing values were replaced by their conditional means predicted from regression models incorporating observed covariates. Quantitative variables were reported as the mean ± standard deviation or as the median and interquartile range, depending on distribution normality. Data with a zero-inflated Poisson distribution were presented as the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. The t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare quantitative variables between groups. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify independent factors associated with readmission or death within 30 days, and death within one year after discharge. Variables with p<0.01 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model using a stepwise forward selection approach (p<0.05), based on maximum likelihood estimation. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the multivariate model. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

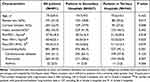

A total of 891 inpatients with COPD as the primary diagnosis were analyzed from 12 secondary hospitals and 4 tertiary hospitals. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, who were predominantly older smokers.

|

Table 1 Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of AECOPD Inpatients† |

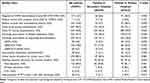

Process Quality of Diagnosis, Comprehensive Assessment and Management for COPD

As shown in Table 2, only 14.3% of COPD inpatients underwent post-bronchodilator spirometry either before or during hospitalization. This rate was significantly lower in secondary hospitals compared to tertiary hospitals (6.6% vs 26.5%, p<0.001). Only 2.2% of patients underwent repeat post-bronchodilator spirometry within one year after discharge. The history of exacerbations was recorded in only 16.8% of medical records. Symptom scores using the the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale or the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) were documented in only 1.2% of cases. Computed tomography (CT) and chest X-ray were performed during hospitalization in 30.0% and 50.8% of patients, respectively.

|

Table 2 Process Quality of Medical Care for AECOPD Inpatients† |

Inhaled medications were included in 37.3% of discharge prescriptions, with a higher proportion in tertiary hospitals than in secondary hospitals (51.7% vs 28.2%, p<0.001). Long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) were prescribed to 30.3% of patients at discharge, more frequently in tertiary hospitals than in secondary hospitals (48.0% vs 19.1%, p<0.001). The most common regimen was a long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroids (LABA/ICS) combination (18.0%), followed by triple therapy (6.7%), and long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) monotherapy (5.6%).

A higher proportion of patients in tertiary hospitals received noninvasive mechanical ventilation compared to secondary hospitals (12.2% vs 3.1%, p<0.001). Smoking cessation education was provided to 88.3% of current smokers, with a higher proportion in tertiary hospitals than in secondary hospitals (91.6% vs 69.7%, p<0.001). The majority of education was delivered verbally, and only 2.9% of patients received counseling based on the 5A method, as recommended by guidelines.12

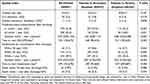

Outcome Quality of Inpatients with COPD Exacerbations

As shown in Table 3, the mean length of hospital stay was 8.5 ± 5.1 days, and 3.3% of patients were admitted to the ICU. During one year of follow-up, 41.8% of patients experienced at least one moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbation. A significantly higher proportion of patients in secondary hospitals experienced exacerbations after discharge compared to those in tertiary hospitals (47.0% vs 33.4%, p<0.001). A total of 23.0% of patients experienced two or more moderate-to-severe exacerbations during follow-up. The median time to the next moderate-to-severe exacerbation was 353 (120, 673) days. The readmission rates for COPD exacerbations at 30 days, 90 days, and one year after discharge were 7.1%, 17.1%, and 39.5%, respectively. The average number of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations within one year after discharge was 0.75 (95% CI 0.67–0.83). All-cause mortality was 2.9% within 30 days and 7.2% within one year.

|

Table 3 Outcome Quality of Medical Care for AECOPD Inpatients† |

Prognostic Factors in Hospitalized Patients with COPD

Multivariate analysis showed that the risk of readmission or death within 30 days after discharge was significantly lower in patients who received a LABD prescription at discharge (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29–0.90, p=0.020), and significantly higher in older patients (Table 4). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated a good model fit (Chi-square 3.17, p=0.205).

|

Table 4 Factors Associated with Increased Readmission or Death Within 30 days After Discharge |

Cardiovascular disease (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.24–4.41, p=0.008) and older age (OR 1.42 per 10 years, 95% CI 1.06–1.90, p=0.018) were associated with a higher risk of death within one year of discharge among patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation (Supplemental Table 1). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test confirmed a good fit of the model (Chi-square 2.700, p=0.259).

Discussion

In this multi-center real-world study, suboptimal quality of care was observed for inpatients diagnosed with COPD in public general hospitals in China. More than 85% of patients lacked post-bronchodilator spirometry to confirm the diagnosis. Documentation of exacerbation history and symptom scores was found in only 16.8% and 1.2% of medical records, respectively. Long-term maintenance therapy after discharge was insufficient, with only 30% of patients prescribed LABDs. We found superior performance in both care process metrics and clinical outcomes within tertiary versus secondary hospitals. However, multivariable analysis identified patient age, cardiovascular comorbidities, and LABDs prescription at discharge as independent prognostic determinants, rather than hospital level. These findings highlight the need for improved standardization of care, particularly in secondary hospitals.

In accordance with GOLD guidelines, patients with COPD should undergo pulmonary function testing to confirm the diagnosis and repeat it at least annually to evaluate the response to treatment.12 A previous nationwide study showed only, 5.9% of COPD patients underwent spirometry.13 This may be partly due to the fact that over 90% of COPD cases are mild to moderate,14 and many of these patients are asymptomatic and do not seek medical attention.14 The low rate of spirometry observed in this study may be explained by the following two reasons: a notable proportion of Chinese patients first present for medical evaluation during acute exacerbations (when pulmonary function testing is contraindicated), and clinicians’ failure to initiate standard diagnostic workup during stable-phase encounters. Effective screening of high-risk groups may help achieve earlier diagnosis and treatment, potentially reducing hospital admissions. Several screening tools, including questionnaires and peak expiratory flow measurements, have been found to be feasible in low- and middle-income countries.15 Our findings underscore the need for enhanced clinician education programs focused on diagnostic protocol adherence, particularly emphasizing spirometry utilization during stable disease phases in respiratory medicine practice. It is also important for physicians to educate patients on the value of regular spirometry during follow-up.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to assess whether clinicians adequately evaluated COPD during inpatient exacerbations in real-world clinical practice in China. Symptom scores and exacerbation history form the basis of initial treatment and are important references for follow-up therapy12 as well as indicators of disease activity and mortality.16 However, we found that few medical records contained this information, which may explain the low proportion of patients prescribed long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) at discharge. It is encouraging that over 80% of patients received a chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan during hospitalization, which contributed to differential diagnosis and provided prognostic and comorbidity data.17,18 These findings highlight the need to improve disease assessment through enhanced physician education. Similarly, deficiencies were observed in standardizing patient education. Most current smokers received verbal smoking cessation advice rather than counseling based on the 5A method recommended in clinical guidelines,12,19 which offers a structured approach to quitting.19 Education on inhaler use was also suboptimal, with the coverage rate among users falling below the ideal level of 100%, indicating room for improvement.

For the first time, our study showed that prescribing inhaled LABDs at discharge was associated with nearly a 50% reduction in readmission or mortality within 30 days. A series of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of LABDs, with or without inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), in improving symptoms and lung function and in reducing exacerbations and hospital admissions in stable COPD.20–23 Our findings support early initiation of LABDs immediately after discharge for COPD exacerbations. However, fewer than 40% of inpatients received LABDs at discharge, indicating an unmet need. Previous studies have reported poor adherence to GOLD guidelines among pulmonologists and low adherence to inhalers by patients with COPD.24–26 A prospective observational study further revealed that inappropriate prescriptions not aligned with guidelines were more common than non-adherence or inhaler misuse.27 Therefore, it is essential to review maintenance therapy, primarily involving inhaled bronchodilators, and reassess inhaler technique before discharge.

Most patients with COPD have at least one additional, clinically relevant chronic disease and die from non-respiratory disorders, particularly cardiovascular diseases and cancer.28 In this study, up to 90% of inpatients with COPD exacerbation had comorbidities, with over 60% having cardiovascular disease, which doubled the one-year risk of death following discharge. Cardiovascular mortality accounts for more than one-quarter of deaths in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.29 Mortality due to cardiac disease in patients with moderate COPD was higher than mortality related to respiratory failure.30 Our findings underscore the importance of including comorbidity management, especially cardiovascular disease, as a process indicator for quality COPD care to reduce mortality.

Our results highlight the need to improve the overall quality of COPD care. Notably, both process measures and outcome indicators were generally better in tertiary hospitals than in secondary hospitals. However, hospital level was not an independent predictor of 30-day readmission or death, nor of one-year mortality. This aligns with previous studies showing no significant association between hospital resources or organizational structure and COPD readmission rates.31,32 In our analysis, key factors influencing prognosis included patient age, comorbidities, and the quality of care processes—specifically, whether LABDs were prescribed. Therefore, improving patient outcomes depends not on encouraging treatment at tertiary hospitals, but on enhancing the quality of COPD care at secondary hospitals, which serve as the main providers of care for common diseases, particularly in smaller cities. National audit data from the United Kingdom suggested that improvements in process indicators occurred only when quality training and performance targets were linked to financial incentives.33 More region-specific studies are needed to identify effective strategies for improving COPD care.

This study has several strengths. It is the first large-scale, multi-center longitudinal survey to evaluate the medical quality of COPD inpatient care in China. We are also the first to examine how in-hospital care quality affects both short- and long-term outcomes of COPD exacerbations. Previous research on prognosis has mostly focused on specific treatments. Additionally, this study included both secondary and tertiary hospitals, whereas most clinical studies lack data from secondary facilities. Furthermore, this is a real-world study with a median follow-up period of nearly two years, and the findings are likely to be representative.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design may introduce recall bias. To reduce this, we used a large sample size across multiple centers. Moreover, the primary outcomes—readmission and death—were mostly derived from medical records and thus less affected by recall bias. Second, due to data limitations, we only analyzed the effect of discharge prescriptions (medications within one month) rather than long-term maintenance treatment. To further examine the impact of healthcare quality control on disease outcomes, a multi-center, prospective, cluster-randomized controlled trial has been initiated.

Conclusion

Management of COPD exacerbations in China revealed deficiencies in care process. Physician practices were inadequate, as indicated by low rates of post-bronchodilator spirometry, symptom scoring, exacerbation history documentation, and structured smoking cessation education. Greater emphasis should be placed on the discharge prescription of inhaled LABDs, which was associated with a 50% reduction in readmission or mortality within 30 days. Cardiovascular comorbidities, which contributed significantly to one-year mortality, must also be addressed. To improve outcomes and reduce healthcare burden, clinician training based on standardized protocols should be prioritized, especially in secondary hospitals.

Data Sharing Statement

All methodologies and raw data can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank for the great work of all the sub-centers investigators. The authors are grateful for the review and guidance provided by Professor John Hurst.

Funding

This study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200044, 82270044), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (C2017050), State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Medical University (Project No.SKLRD-Z-202317).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

2. Mannino DM, Roberts MH, Mapel DW, et al. National and local direct medical cost burden of COPD in the United States From 2016 to 2019 and projections through 2029. Chest. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.040

3. Zhu B, Wang Y, Ming J, et al. Disease burden of COPD in China: a systematic review. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2018;13:1353–1364.

4. Boers E, Barrett M, G SJ, et al. Global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease through 2050. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2346598. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46598

5. Kong CW, Wilkinson T. Predicting and preventing hospital readmission for exacerbations of COPD. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2):00325–2019. doi:10.1183/23120541.00325-2019

6. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3). doi:10.1183/13993003.00791-2016

7. Tzanakis N, Koulouris N, Dimakou K, et al. Classification of COPD patients and compliance to recommended treatment in Greece according to GOLD 2017 report: the RELICO study. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):216. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01576-6

8. Palli SR, Zhou S, Shaikh A, et al. Effect of compliance with GOLD treatment recommendations on COPD health care resource utilization, cost, and exacerbations among patients with COPD on maintenance therapy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(5):625–637. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2021.20390

9. Wang Z, Locantore N, Haldar K, et al. Inflammatory endotype-associated airway microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical stability and exacerbations: a multicohort longitudinal analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(12):1488–1502. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009-3448OC

10. I RA, Definition WJA. Causes, pathogenesis, and consequences of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(3):421–438. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2020.06.007

11. Sivapalan P, S LT, Janner J, et al. Eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted to hospital with COPD exacerbation (CORTICO-COP): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):699–709. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30176-6

12. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease, inc. global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2024 REPORT)[EB/OL] (2023-11-13). Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/.

13. Fang L, Gao P, Bao H, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a nationwide prevalence study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(6):421–430. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30103-6

14. Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):721–732. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61290-3

15. Siddharthan T, L PS, A QS, et al. Discriminative accuracy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease screening instruments in 3 low- and middle-income country settings. JAMA. 2022;327(2):151–160. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23065

16. Celli B, Locantore N, C YJ, et al. Markers of disease activity in COPD: an 8-year mortality study in the ECLIPSE cohort. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(3):2001339. doi:10.1183/13993003.01339-2020

17. Martínez-García MÁ, de la Rosa-Carrillo D, Soler-Cataluña J, et al. Bronchial infection and temporal evolution of bronchiectasis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(3):403–410. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa069

18. Ezponda A, Casanova C, Divo M, et al. Chest CT-assessed comorbidities and all-cause mortality risk in COPD patients in the BODE cohort. Respirology. 2022;27(4):286–293. doi:10.1111/resp.14223

19. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. public health service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–176. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009

20. Muro S, Yoshisue H, Kostikas K, et al. Indacaterol/glycopyrronium versus tiotropium or glycopyrronium in long-acting bronchodilator-naive COPD patients: a pooled analysis. Respirology. 2020;25(4):393–400. doi:10.1111/resp.13651

21. Halpin D, T DM, K HM, et al. The effect of exacerbation history on outcomes in the IMPACT trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):1901921. doi:10.1183/13993003.01921-2019

22. Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

23. Celli BR, Anderson JA, Cowans NJ. Pharmacotherapy and lung function decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(6):689–698. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-1854OC

24. Ierodiakonou D, Sifaki-Pistolla D, Kampouraki M, et al. Adherence to inhalers and comorbidities in COPD patients. A cross-sectional primary care study from Greece. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):253. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-01296-3

25. Humenberger M, Horner A, Labek A, et al. Adherence to inhaled therapy and its impact on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):163. doi:10.1186/s12890-018-0724-3

26. Sandelowsky H, M WU, B AB, et al. COPD - do the right thing. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):244. doi:10.1186/s12875-021-01583-w

27. P CK, W KF, S CH, et al. Adherence to a COPD treatment guideline among patients in Hong Kong. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3371–3379. doi:10.2147/COPD.S147070

28. M FL, R CB, Agusti A, et al. COPD and multimorbidity: recognising and addressing a syndemic occurrence. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(11):1020–1034. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00261-8

29. P ML, John M, A AJ, et al. Ascertainment of cause-specific mortality in COPD: operations of the TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Thorax. 2007;62(5):411–415. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.072348

30. Andre S, Conde B, Fragoso E, et al. COPD and Cardiovascular Disease. Pulmonology. 2019;25(3):168–176. doi:10.1016/j.pulmoe.2018.09.006

31. Connolly MJ, Lowe D, Anstey K, et al. Admissions to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect of age related factors and service organisation. Thorax. 2006;61(10):843–848. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.054924

32. Hosker H, Anstey K, Lowe D, et al. Variability in the organisation and management of hospital care for COPD exacerbations in the UK. Respir Med. 2007;101(4):754–761. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.016

33. Hurst JR, Quint JK, Stone RA, et al. National clinical audit for hospitalised exacerbations of COPD. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(3). doi:10.1183/23120541.00208-2020

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Prevalence, Risk Factor and Clinical Characteristics of Venous Thrombus Embolism in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of COPD: A Prospective Multicenter Study

Liu X, Jiao X, Gong X, Nie Q, Li Y, Zhen G, Cheng M, He J, Yuan Y, Yang Y

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023, 18:907-917

Published Date: 18 May 2023

Red Blood Cell Distribution Width/Hematocrit Ratio: A New Predictor of 28 Days All-Cause Mortality of AECOPD Patients in ICU

Long Z, Zeng Q, Ou Y, Liu Y, Hu J, Wang Y, Wang Y

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2024, 19:2497-2516

Published Date: 22 November 2024