Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 18

Traditional Bullying Victimization and Cyberbullying Perpetration: the Role of Anger Rumination and Self-Control

Authors Jiang H, Jin Y, Yang Q

Received 20 November 2024

Accepted for publication 13 March 2025

Published 7 April 2025 Volume 2025:18 Pages 877—886

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S507510

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Gabriela Topa

Huaibin Jiang,1 Yinchuan Jin,2,3 Qun Yang2

1School of Education, Fujian Polytechnic Normal University, Fuzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Clinical Psychology, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, People’s Republic of China; 3Innovation Research Institute, Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University, Shaanxi, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yinchuan Jin, Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medical Psychology, Fourth Military Medical University, No. 169, Changle West Road, Xincheng District, Xi’an, Shaanxi, 710032, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected] Qun Yang, Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medical Psychology, Fourth Military Medical University, No. 169, Changle West Road, Xincheng District, Xi’an, Shaanxi, 710032, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Background: The transition from being a victim of traditional bullying to engaging in cyberbullying is an emerging area of research. However, not all adolescents who experience traditional bullying go on to perpetrate cyberbullying. Grounded in the General Aggression Model, this study investigates the longitudinal association between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration, focusing on the underlying mechanisms.

Methods: In a longitudinal design, 442 middle school students (49.80% female, Mage = 13.02, SD = 0.85) completed a survey including the Victim Scale, Anger Rumination Scale, Self-Control Scale, and Cyberbullying Scale at baseline enrollment and at six-month follow-up.

Results: Key findings include: (1) T1 Traditional bullying victimization did not directly predict later T2 cyberbullying perpetration; (2) T2 Anger rumination mediated the relationship between T1 traditional bullying victimization and T2 cyberbullying perpetration; (3) T1 Self-control moderated the link between T2 anger rumination and T2 cyberbullying perpetration, with stronger association observed in adolescents with lower self-control.

Conclusion: These results highlight crucial pathways from traditional bullying victimization to cyberbullying perpetration in adolescents.

Keywords: traditional bullying victimization, anger rumination, self-control, cyberbullying perpetration

Introduction

The advent of the digital age has profoundly impacted people’s lives, particularly those in middle school settings. As digital natives, adolescents benefit from the convenience and wealth of information available on the Internet but are also vulnerable to cyberbullying, which involves harmful behaviors enacted through digital platforms such as the Internet or mobile phones.1 Adolescents are at a critical developmental stage characterized by unbalanced physical and mental growth and limited cognitive abilities.2 The anonymity provided by cyberspace facilitates the perpetration of cyberbullying and complicates efforts to address and mitigate its impact. Both perpetrators and victims of cyberbullying may suffer from psychological and behavioral issues such as anxiety and social withdrawal, which can impede their mental health and social interactions.3,4 Research has identified a relationship between being bullied and being a bully.5,6 While the global prevalence of cyberbullying is well documented, traditional bullying victimization remains a significant issue, particularly in school contexts. Traditional bullying, characterized by physical and verbal aggression, continues to affect a large number of adolescents, and its consequences often extend to the digital realm, facilitating the onset of cyberbullying behaviors. The association between traditional bullying victimization and subsequent cyberbullying perpetration has been explored in several studies.7 However, much of the existing research in this area has been conducted in Western contexts, where cultural, social, and educational dynamics may differ from those in Asian schools. Recent studies indicate that the factors influencing bullying behaviors in Asian contexts, such as the influence of collectivist values, teacher-student relationships, and family dynamics, may play a unique role in shaping bullying experiences.8–10 These studies highlight the need for further investigation into how traditional bullying victimization in Asian schools contributes to cyberbullying perpetration and the mechanisms that drive this process.

Given the distinct cultural and social dynamics within Asian school settings, it is essential to explore these issues in more depth. Although the relationship between traditional bullying and cyberbullying has been established, there is a lack of research that delves into the specific pathways linking traditional bullying victimization to cyberbullying, particularly within the Asian context. Understanding these pathways is crucial for developing culturally appropriate and effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how traditional bullying victimization leads to cyberbullying perpetration, with a focus on the mediating role of anger rumination and the moderating role of self-control. In doing so, it hopes to contribute both theoretically and practically to the reduction of cyberbullying among adolescents in Asia.

Traditional Bullying Victimization and Cyberbullying Perpetration

Traditional bullying victimization involves ongoing aggressive behavior repeatedly targeted at an individual, often accompanied by a power imbalance.11 The General Aggression Model (GAM), rooted in social learning and social cognitive theories, suggests that situational experiences, such as being bullied, can impact aggression through cognitive and emotional processes.12 Victims of traditional bullying might adopt aggressive behaviors after observing how they are treated, potentially using bullying as a maladaptive response to conflict.13 While research has identified a clear link between traditional bullying victimization and later bullying perpetration,5 growing evidence indicates that such victims may be more inclined to engage in cyberbullying as an act of retaliation.14

The anonymity of cyberspace reduces the risk of retaliation in real life, which makes cyberbullying an attractive avenue for traditional bullying victims. Chu et al emphasize that the connection between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration may surpass the relationship between victimization and subsequent traditional bullying.14 Other studies also report this positive association, where traditional bullying victims engage in cyberbullying as a means to assert control or retaliate.7,15 However, some research suggests that not all victims resort to cyberbullying perpetration,16 indicating potential boundary conditions that may influence the relationship between victimization and perpetration. For example, individual differences in empathy, anger rumination, or environmental factors such as peer influence may play a role in determining whether victims turn to cyberbullying.17

Anger Rumination as a Mediator

According to the General Aggression Model (GAM), traditional bullying victimization can drive cyberbullying perpetration primarily through triggering aggression-related cognitions, sensations, and arousal. Anger rumination, defined as the tendency to dwell on anger-provoking events and their implications unconsciously,18 is a cognitive mechanism closely associated with anger but remains relatively distinct.19 Victims of traditional bullying often revisit their experiences repeatedly in an effort to make sense of them, which can lead to anger rumination.20 Moreover, such individuals may process information in ways that reinforce hostile thought patterns, further fostering anger rumination.21 This cognitive bias, characterized by a focus on hostility, can contribute to cyberbullying perpetration.22 Additionally, continually reflecting on anger-inducing events may amplify emotional distress, thereby increasing the likelihood of engaging in cyberbullying.23 Research suggests that anger rumination mediates the link between bullying victimization and aggressive behavior and has been shown to play a mediating role between cyber victimization and cyberbullying perpetration.21,24 However, its mediating between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration remains to be fully explored.

Self-Control as a Moderator

The General Aggression Model (GAM) posits that individual characteristics (eg, self-control) and environmental influences (eg, victimization from traditional bullying) shape adolescents’ cognitive processes (eg, anger rumination) and behaviors (eg, engaging in cyberbullying).13 Self-control, defined as the capacity to manage or modify one’s responses, is essential for achieving adaptive and socially acceptable outcomes.25 Strong self-control enhances the ability to suppress anger-related rumination,26 allowing individuals to focus more effectively on goal-directed activities while minimizing intrusive, ruminative thoughts. In contrast, those with poor self-control may struggle to regulate future-oriented thoughts, leading to increased rumination.27,28 Research indicates that high self-control mitigates tendencies toward anger and aggressive behavior, disrupting cycles of rumination and alleviating negative emotional states.29 Furthermore, self-control moderates the link between anger rumination and cyberbullying.30 Specifically, low self-control exacerbates the connection between anger rumination and cyberbullying behavior, whereas high self-control individuals are better equipped to regulate their temper and impulses, diminishing the influence of anger rumination on cyberbullying tendencies.

The Present Study

Previous research has investigated the link between being a victim of traditional bullying and later engaging in cyberbullying perpetration. However, much of this work relies on cross-sectional designs, which do not allow for establishing a definitive causal relationship between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration. Moreover, the roles of anger rumination and self-control in this process remain underexplored. While some findings indicate that anger rumination may intensify victims’ negative perceptions of bullying, thereby increasing their propensity to perpetrate cyberbullying,24 these studies often focus on isolated psychological factors without examining the interplay between anger rumination and self-control. To address these gaps, this study adopts a longitudinal approach to investigate the mechanisms linking traditional bullying victimization to cyberbullying perpetration, considering both anger rumination and self-control.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The study sampled students from two middle schools in Fujian, China. Initially, a representative city in Fujian Province was selected as the target community. Within this community, two middle schools with comparable characteristics in terms of size, teaching quality, and student demographics were randomly chosen. In each school, four classes were randomly selected, and two waves of surveys were conducted in April 2023 (T1) and October 2023 (T2). A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure the broad representativeness of the sample. The surveys were administered by trained graduate students who obtained consent from the participants and their parents one week prior. At T1, 486 valid questionnaires were collected, and at T2, 422 valid follow-up questionnaires were gathered. The dropout rate was 13.17%, with 64 participants lost between T1 and T2. No significant differences were found in bullying, anger rumination, self-control, or cyberbullying scores between those who dropped out and those who completed both surveys. The participants were aged between 12 and 16 years (Mage = 13.02, SD = 0.85), with 210 females (49.80%). The data collection procedures received approval from the Ethics Committee of the first authors’ institution. Additionally, six months have been used as an appropriate longitudinal period in prior studies.31,32

Measures

Victim Scale

The Chinese adaptation of the Victim Questionnaire was employed to assess experiences of traditional bullying victimization.11,33 This instrument includes six items, each rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 4 = “more than four times”). An example question is: “Have classmates ever kicked, pushed, or threatened you?” Higher aggregate scores reflect greater victimization levels. The scale has been validated with adolescents, showing satisfactory reliability and validity.7 In this research, Cronbach’s α was 0.76.

Anger Rumination Scale

Anger rumination was measured using the Anger Rumination Scale.18,34 This scale consists of 19 items, each rated on a 4-point scale (1 = “never”, 4 = “always”). One sample item reads: “I repeatedly think about situations that made me angry”. Higher total scores signify higher tendencies for anger rumination. Prior studies have confirmed its psychometric soundness among adolescents.35 The Cronbach’s α coefficient in the present study was 0.94.

Self-Control Scale

The Self-Control Scale in its Chinese version was utilized to measure levels of self-control.36,37 It comprises 13 items, scored on a 4-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 4 = “strongly agree”). A sample statement is: “Others think I exhibit strong self-discipline”. Items 8 and 10 are reverse-coded. Higher overall scores indicate better self-control. This scale has demonstrated robust reliability and validity in prior research.38 In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.72.

Cyberbullying Scale

Cyberbullying perpetration was assessed using the Cyberbullying Scale.39,40 The scale includes six items rated on a 4-point scale (1 = “never”, 4 = “several times a week”). A representative item is: “I share others’ private information online”. Higher total scores correspond to higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the scale.7 In this research, Cronbach’s α was 0.78.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted using SPSS 25.0 to explore the fundamental characteristics and interrelations among the variables. The mediation of anger rumination between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration was examined using Model 4 from Hayes’ PROCESS macro.41 Additionally, the moderating role of self-control in the link between anger rumination and cyberbullying perpetration was analyzed through Model 14. Gender was controlled for in the analysis to account for its potential influence on the study variables.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To address the issue of potential common method bias, which may arise from self-reported measures, diagnostic testing was performed. Harman’s single-factor test was utilized to evaluate common method bias across all items related to the four variables: traditional bullying victimization, anger rumination, self-control, and cyberbullying perpetration. Consistent with the threshold of 40%,42 the analysis revealed ten factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor accounted for 22.61% of the total variance, significantly below the critical 40% cutoff. These findings suggest that common method bias is not a major concern in this study.

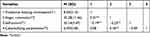

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Correlation results show that traditional bullying victimization at T1 is positively associated with anger rumination at T2. Anger rumination at T2, in turn, is positively linked to cyberbullying perpetration, while self-control at T1 is negatively associated with anger rumination at T2.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics |

Mediation Analysis

Figure 1 presents the mediation analysis results. Traditional bullying victimization at T1 was found to significantly predict anger rumination at T2, which, in turn, significantly predicted cyberbullying perpetration at T2. Bootstrap testing with a 95% confidence interval revealed that anger rumination completely mediated the link between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration (ab = 0.06, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.180]). The mediation effect accounted for 83.64% of the total effect.

|

Figure 1 Mediation of Anger Rumination. Note. ***p<0.001. |

Moderated Mediation Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the moderation analysis findings. Traditional bullying victimization significantly associated with anger rumination, which then significantly predicted cyberbullying perpetration. Additionally, the interaction between self-control and anger rumination was a significant predictor of cyberbullying perpetration, suggesting that self-control moderates this pathway.

|

Figure 2 Moderated Mediation of Self-control. Note. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. |

A simple effects analysis further explored the moderating role of self-control, as shown in Figure 3. When self-control was low (−1 SD), the link between anger rumination and cyberbullying perpetration was stronger (Bsimple = 0.30, t = 4.88, p < 0.001). Conversely, at high levels of self-control (+1 SD), the link became negligible (Bsimple = −0.01, t = −0.06, p > 0.05).

|

Figure 3 Simple slope analysis. |

Discussion

To better understand the link between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying, this study explores their longitudinal relationship, focusing on the mechanisms and conditions under which traditional bullying victimization associated with cyberbullying perpetration. The findings partially validate the hypotheses, revealing that while traditional bullying victimization does not directly lead to cyberbullying perpetration, it exerts an indirect link through anger rumination. Additionally, self-control moderates the relationship between anger rumination and cyberbullying perpetration.

Traditional Bullying Victimization and Cyberbullying Perpetration

The results reveal no direct association between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration six months later, contradicting Hypothesis 1. This finding aligns with studies such as Raskauskas and Stoltz,16 which suggest that traditional bullying victims may not necessarily transition into cyberbullying roles. Traditional bullying is typified by repeated victimization and power imbalances,11 and the psychological impact of such experiences, including learned helplessness, may discourage victims from retaliating through cyberbullying. Learned helplessness, a state where individuals perceive themselves as powerless to change their circumstances, might render traditional bullying victims less likely to exploit the anonymity and perceived safety of cyberspace to perpetrate bullying behaviors. Contrastingly, Juvonen and Gross observed that students frequently targeted at school are significantly more likely to experience online bullying.43 This highlights the interconnectedness of offline and online environments, underscoring the role of cyberspace as an extension of school-based dynamics rather than an isolated risk domain. In conclusion, the absence of a direct link between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration may reflect the complex interplay of psychological, social, and contextual factors that shape victim responses. While cyberspace serves as an extension of school-based interactions, the transition from victimization to perpetration is not uniform and is likely contingent upon a range of individual and environmental influences. Understanding these nuances is critical for developing targeted interventions to break the cycle of bullying across contexts.

The Mediating Role of Anger Rumination

However, traditional bullying victimization can indirectly influence cyberbullying perpetration through anger rumination, which supports Hypothesis 2. Bullying victimization, as a strong negative stimulus, can harm adolescents’ emotional regulation. It can immerse them in negative experiences and anger, resulting in repetitive negative thinking.20,44 This ongoing rumination on anger not only intensifies the severity and duration of negative emotions but can also, to some extent, weaken the inhibitory effect of learned helplessness.45 Anger rumination keeps individuals focused on the unfairness and anger related to their bullying experiences, increasing dissatisfaction and hostility toward perpetrators and the environment, thereby reinforcing the sense of injustice about their victimization.20 Moreover, anger rumination can lead to a biased processing of information, increasing anger. This impairs an individual’s assessment and decision-making about experienced events and increases the risk of aggressive behavior.46 In this emotional state, victims may develop a strong desire for revenge or emotional release, particularly in the online environment, where such desires are more easily activated. The anonymity and concealment of cyberspace make adolescents more prone to engage in cyberbullying and cyber retaliation as a way to retaliate and vent.22,24

Therefore, anger rumination can be seen as a key mediating mechanism that not only intensifies victims’ negative emotions but also weakens the inhibitory effect of learned helplessness on cyberbullying behavior, thereby indirectly linking traditional bullying victimization to cyberbullying behavior.

The Moderating Role of Self-Control

This study confirms Hypothesis 3 by demonstrating that self-control moderates the link between anger rumination and cyberbullying perpetration. From the perspective of self-control resources, self-control reflects an individual’s stable resource capacity.47 Individuals with low self-control tend to have fewer baseline resources available for regulating their emotions and impulses compared to those with high self-control.48,49 Consequently, when experiencing the same level of anger rumination, individuals with lower self-control often lack the resources needed to manage their emotions and suppress impulsive behaviors, making them more susceptible to engaging in cyberbullying. Conversely, individuals with high self-control possess a greater reserve of resources. Even when experiencing resource depletion, their stronger self-regulatory capacity allows them to better manage their behavior and resist engaging in cyberbullying.

From the perspective of behavioral responses, individuals with high self-control respond differently to resource depletion compared to those with low self-control. High self-control individuals can shift their attention away from stimuli that cause depletion, focusing instead on other matters.50 This ability means that during episodes of anger rumination, individuals with high self-control are more likely to consider the consequences of their actions and adhere to societal norms and ethical principles.51 They can effectively interrupt the rumination process, reducing the likelihood of cyberbullying. In contrast, adolescents with low self-control often lack robust self-regulation standards and fail to evaluate the appropriateness of their behavior consciously. The anonymity of the online environment provides them with a sense of “security”, encouraging impulsive actions without considering the repercussions, thereby increasing their likelihood of cyberbullying.52

Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations. First, the use of a longitudinal design, while helpful in exploring trends over time, does not provide strong evidence for causality.53 As such, future research would benefit from employing more rigorous experimental designs to better understand the causal relationship between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration. Second, unobserved individual-level factors (such as personality, mental health history, and coping mechanisms) and family-level factors (such as parenting style, socioeconomic background, and family stressors) may significantly influence traditional bullying victimization and subsequent behaviors, such as cyberbullying perpetration. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Future research should incorporate these factors and utilize longitudinal or multilevel models to further explore their impact. Third, this study use different time points for measuring self-control (T1) and anger rumination (T2). Although previous research has supported the use of T1 for moderating variables and T2 for mediating variables, this design choice limits our ability to directly assess changes in these variables over time. Future research could consider using more consistent time points to measure both self-control and anger rumination, allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of their dynamic interactions. Forth, this study did not include measures of traditional bullying perpetration or cyberbullying victimization. This omission may limit our understanding of the interplay between these behaviors and the primary constructs investigated. Future research should consider incorporating these measures to provide a more comprehensive analysis. Lastly, the sample in this study was limited to adolescents from Fujian, China, meaning that the results may not be generalizable to other regions or cultural contexts. To strengthen the external validity of the conclusions, future studies should include a broader and more diverse sample, spanning different geographical locations and cultural backgrounds.

Implications

Despite its limitations, this study makes significant contributions to both theoretical understanding and practical applications. Theoretically, it is the first to employ a longitudinal design to explore the relationship between traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration, offering a fresh perspective on this complex issue. By integrating the GAM, this research extends the existing literature by examining how traditional bullying victimization is linked with cyberbullying perpetration, bridging the gap between traditional and online aggression frameworks. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on environmental or social factors, this study highlights the significant role of anger rumination as a cognitive-emotional mechanism that could help explain the connection between victimization and aggressive online behaviors.

Practically, these findings provide a foundation for developing targeted intervention strategies. By focusing on enhancing adolescents’ self-control and promoting healthier emotional regulation, such interventions could effectively mitigate the risk of cyberbullying perpetration. Moreover, the study offers insights for designing prevention programs that address both the immediate emotional consequences of bullying victimization and the long-term cognitive patterns that may perpetuate aggression in digital contexts. This integrated approach holds promise for reducing cyberbullying behaviors and fostering safer online environments for adolescents.

Data Sharing Declaration

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Polytechnic Normal University (2022-003) and all methods were complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. We have obtained the informed consent from the study participants and the parents/legal guardians.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the schools, teachers, parents, and adolescents for their invaluable support in making this research possible.

Funding

This research was supported by the Joint Founding Project of Innovation Research Institute of Xijing Hospital (LHJJ24XL09) and Rapid Response Project of Air Force Medical University (2023KXKT057).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1. Smith PK, Slonje R. Cyberbullying: the nature and extent of a new kind of bullying, in and out of school. In: Jimerson SR, Swearer SM, Espelage DL, editors. Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective. New York: Routledge; 2009:249–262.

2. Larsen B, Luna B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;94:179–195. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.005

3. Anyerson SGT, Jorge ER, Lesmes GZ. The effect of bullying and cyberbullying on predicting suicide risk in adolescent females: the mediating role of depression. Psychiatry Res. 2024;337:115968. doi:10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2024.115968

4. Elizabeth C, Estefanía E, Martínez-Monteagudo MC, Beatriz D. Emotional adjustment in victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Soc Psychol Edu. 2020;23(4):917–942. doi:10.1007/s11218-020-09565-z

5. Camacho A, Runions K, Ortega-Ruiz R, et al. Bullying and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: prospective within-person associations. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52:406–418. doi:10.1007/s10964-022-01704-3

6. Falla D, Ortega-Ruiz R, Runions K, Romera EM. Why do victims become perpetrators of peer bullying? Moral disengagement in the cycle of violence. Youth Soc. 2022;54(3):397–418. doi:10.1177/0044118X20973702

7. Liang H, Zhu F, Li X, Jiang H, Zhang Q, Xiao W. The link between bullying victimization, maladjustment, self-control, and bullying: a comparison of traditional and cyberbullying perpetrator. Youth Soc. 2024. doi:10.1177/0044118X241247213

8. Son H, Jang H, Park H, Subramanian SV, Kim J. Exploring the trajectories of depressive symptoms associated with bullying victimization: the intersection of gender and family support. J Adolesc. 2024. doi:10.1002/jad.12450

9. Park H, Son H, Jang H, Kim J. Chronic bullying victimization and life satisfaction among children from multicultural families in South Korea: heterogeneity by immigrant mothers’ country of origin. Child Abuse Negl. 2024;151:106718. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106718

10. Kim J, Fong E. The influence of bullying victimization on acculturation and life satisfaction among children from multicultural families in South Korea. J Ethnic Migrat Stud. 2024;50(18):4718–4737. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2359678

11. Olweus D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford: Blackwell; 1993.

12. Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Ann Rev Psychol. 2002;53(1):27–51. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

13. Dewall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Viol. 2011;1(3):245–258. doi:10.1037/a0023842

14. Chu XW, Fan CY, Liu QQ, Zhou ZK. Stability and change of bullying roles in the traditional and virtual contexts: a three-wave longitudinal study in Chinese early adolescents. J Adolesc. 2018;47(11):2384–2400. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0908-4

15. Faye M, Mona K, Tahany G, Joanne D. Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: victims, bullies and bully–victims. Child Youth Services Rev. 2011;34(1):63–70. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.032

16. Raskauskas J, Stoltz AD. Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Develop Psychol. 2007;43(3):564–575. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564

17. Zhu W, Lu D, Li C, Tian X, Bai X. Longitudinal associations between ostracism, anger rumination, and social aggression. Curr Psychol. 2023;43(4):3158–3165. doi:10.1007/S12144-023-04279-9

18. Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN. Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31(5):689–700. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9

19. Sourander A, Klomek AB, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Helenius H. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):720–728. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.79

20. Schacter HL, Juvonen J. The effects of school-level victimization on self-blame: evidence for contextualized social cognitions. Develop Psychol. 2015;51(6):841–847. doi:10.1037/dev0000016

21. Quan F, Huang J, Li H, Zhu W. Longitudinal relations between bullying victimization and aggression: the multiple mediation effects of anger rumination and hostile automatic thoughts. Psych J. 2024;13(5):849–859. doi:10.1002/pchj.760

22. Yang J, Li W, Wang W, Gao L, Wang X. Anger rumination and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: moral disengagement and callous-unemotional traits as moderators. J Affect Disorders. 2021;278:397–404. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.090

23. Yang J, Li W, Gao L, Wang X. How is trait anger related to adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration? A moderated mediation analysis. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(9–10):NP6633–NP6654. doi:10.1177/0886260520967129

24. Camacho A, Ortega-Ruiz R, Romera EM. Longitudinal associations between cybervictimization, anger rumination, and cyberaggression. Aggress Behav. 2021;47(3):332–342. doi:10.1002/ab.21958

25. Wills TA, Pokhrel P, Morehouse E, Fenster B. Behavioral and emotional regulation and adolescent substance use problems: a test of moderation effects in a dual‐process model. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):279–292. doi:10.1037/a0022870

26. Hofmann W, Schmeichel BJ, Baddeley AD. Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(3):174–180. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006

27. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(6):351–355. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x

28. Heatherton TF, Wagner DD. Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(3):132–139. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005

29. Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Spinrad TL. Effortful control: relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. Guilford Press; 2011:263–283.

30. Zheng X, Chen H, Wang Z, Xie F, Bao Z. Online violent video games and online aggressive behavior among Chinese college students: the role of anger rumination and self‐control. Aggress Behav. 2021;1–7. doi:10.1002/ab.21967

31. Leung CJ, Cheng L, Yu J, Yiend J, Lee TMC. Six‐month longitudinal associations between cognitive functioning and distress among the community‐based elderly in Hong Kong: a cross‐lagged panel analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;265:77–81. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.045

32. Zhang R, Chen J, Zhang C, Xu W. Longitudinal association of mindfulness with aggression and non‐suicidal self‐injury in adolescence: the mediating role of shame‐proneness. Aggress Behav. 2024;50:e22121. doi:10.1002/ab.22121

33. Zhang WX, Wu JF, Kevin J. Revision of the Chinese version of olweus child bullying questionnaire. Psychol Dev Edu. 1999;2:8–12. In Chinese. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.1999.02.002

34. Luo Y, Liu Y. The reliability and validity of Chinese version anger rumination scale in college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(4):667–670. In Chinese. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.04.017

35. Tao Y, Niu H, Li Y, et al. Effects of personal relative deprivation on the relationship between anger rumination and aggression during and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a longitudinal moderated network approach. J Adolesc. 2023;95(3):596–608. doi:10.1002/JAD.12140

36. Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Personal. 2004;72(2):271–322. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

37. Tan S, Guo Y. Revision of self-control scale for Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2008;16(5):468–470. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2008.05.022

38. Zhou H, Wei X, Jiang H, et al. The link between exposure to violent media, normative beliefs about aggression, self‐control, and aggression: a comparison of traditional and cyberbullying. Aggress Behav. 2022;1–7. doi:10.1002/ab.22057

39. Shapka JD, Maghsoudi R. Examining the validity and reliability of the cyber-aggression and cyber-victimization scale. Comp Human Behav. 2017;69:10–17. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.015

40. Xie XL, Zhang H, Ju K, Xiao BW, Liu JS, Jennifer DS. Examining the validity and reliability of the short form of cyberbullying and cybervictimization (CAV. Scale Chin J Clin Psychol. 2022;30(5):

41. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

42. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

43. Juvonen J, Gross EF. Extending the school grounds? Bullying experiences in cyberspace. J School Health. 2008;78:496–505. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00335.x

44. Segovia-González M, Ramírez-Hurtado JM, Contreras I. Analyzing the risk of being a victim of school bullying. the relevance of students’ self-perceptions. Child Indic Res. 2023;16:2141–2163. doi:10.1007/s12187-023-10045-x

45. Denson TF. The multiple systems model of angry rumination. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2013;17(2):103–123. doi:10.1177/1088868312467086

46. Hou Y, Li X, Xia L-X. Common mechanisms underlying the effect of angry rumination on reactive and proactive aggression: a moderated mediation model. J Interpers Violence. 2024;39(5–6):1035–1057. doi:10.1177/08862605231201819

47. Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis NLD. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(4):495–525. doi:10.1037/a0019486

48. Dvorak RD, Simons JS. Moderation of resource depletion in the self-control strength model: differing effects of two modes of self-control. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(5):572. doi:10.1177/0146167208330855

49. Muraven M, Collins RL, Shiffman S, Paty JA. Daily fluctuations in self-control demands and alcohol intake. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(2):140–147. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.140

50. de Ridder DT, Lensveltmulders G, Finkenauer C, Stok FM, Baumeister RF. Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2012;16(1):76. doi:10.1177/1088868311418749

51. Jensen-Campbell LA, Knack JM, Waldrip AM, Campbell SD. Do big five personality traits associated with self-control influence the regulation of anger and aggression? J Res Personality. 2007;41(2):403–424. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.05.001

52. Wright MF, Harper BD, Wachs S. The associations between cyberbullying and callous-unemotional traits among adolescents: the moderating effect of online disinhibition. Pers Individ Dif. 2018;140(1):41–45. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.001

53. Mitchell MA, Maxwell SE. A comparison of the cross-sectional and sequential designs when assessing longitudinal mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2013;48(3):301–339. doi:10.1080/00273171.2013.784696

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.