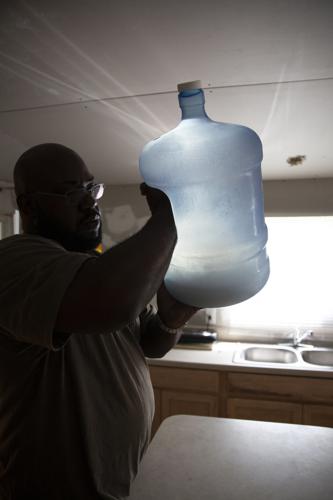

A Bloomington family can’t drink their water while renovating their hurricane torn-home in triple-degree heat.

They drank it until an oil company sent them a letter.

That letter informed Terrance, 42, and Tonja Wortham, 49, that Frostwood Energy, of Houston, had drilled a horizontal well too close to their property.

Recalling their water first appearing black when re-installing toilets and Tonja Wortham’s many hospitalizations for unexplained stomach pain, the couple thought Frostwood contaminated their water by coming too close.

Tests done later confirmed their water was unsafe to drink, but Frostwood denies responsibility for this.

“We are sorry if Mr. Wortham is having problems, but it has nothing to do with Frostwood,” Frostwood’s attorney Matt Jones said. “(This oil) well produces from a point almost a mile below the surface of the earth, and it is at least that far from Mr. Wortham.”

Frostwood has asked the Worthams not to protest an amendment to its permit with the Texas Railroad Commission. It’s even offered them cash and added more zeros on the end of each offer.

The amendment would give Frostwood a pass to violate a rule related to how many feet there must be between a well and someone else’s property line.

So far, the family hasn’t acquiesced, choosing instead to join their neighbors to protest Frostwood in Austin next month. Their next-door neighbor’s water quality has also degraded.

“We have three kids that stay here,” Tonja Wortham said, “(My grandchildren,) a 6-year-old, a 4-year-old and a 1-year-old and my daughter, who is 26, so it’s hard.”

But people who have made the same choice as the Worthams have found it was futile.

Dispute history

About 10 years ago, the Bhandari family protested Chesapeake Energy’s attempt to do the same thing as Frostwood only Chesapeake wanted to hydraulically fracture. It wanted its lateral to go up to the Bhandaris’ home without paying them for their mineral rights and made them a bizarre sales pitch.

“The land man actually said to my husband, ‘Look, you’re not going to make any money signing this deal, but I think you should sign. We’ll give you enough money so you can go to Walmart and buy a big screen TV,’” Ranjana Bhandari, 54, said.

Not needing a TV and concerned about their changing North Arlington neighborhood, they took off work and went to Austin on a weekday instead. What unfolded there, she said, was even more bizarre.

A Railroad Commission employee acted like a judge and let both sides make arguments, but unlike a regular court proceeding, the Bhandaris didn’t know what Chesapeake would say was the reason they had to violate the rule in the first place. They couldn’t prepare to counter. The Railroad Commission employee, referred in this setting to a “hearing examiner,” sided with Chesapeake after Bhandari said its experts presented flawed calculations that showed it would lose a lot of gas if it didn’t get to fracture her and her husband’s property.

“How difficult is it for people like us? It’s really difficult,” said Bhandari, a former economics professor, “and I was in a better position than most because I had a little bit of a math background and had tried really hard to keep them away. Our house was right at the end of the lateral, so we weren’t stopping any of our neighbors from getting their minerals drilled, but even in that scenario, the whole process was predetermined.”

And the numbers seem to bear this out even today.

Records show that of the 28 times Frostwood has asked for an exemption to the spacing rule, it was given an exemption every time except once.

In what the Railroad Commission considers Region 2, which encompasses 15 counties including Victoria, nearly all of the 2,595 exemptions to the spacing rule sought by operators were granted.

Bhandari said if she could recommend anything to others protesting, it would be to hire a lawyer, which she knows is not feasible for everyone. It wasn’t for her and her husband.

Expert advice

Experts the Victoria Advocate talked to about what the Worthams were experiencing also said it might be difficult to prove water was contaminated by oil exploration.

Tim Andruss, the general manager of the Victoria County Groundwater Conservation District, said some have tried to prove that through the years, but one could argue there’s a natural variability in the aquifer.

“In the southern part of the county in and around Bloomington and Placedo, we have measurements that show water quality being less than fresh or poor quality. Some people might use the phrase ‘brackish,’” Andruss said.

He said the best way to make one’s case would be to have a test that showed what the water’s condition was like before the oil exploration.

The Worthams do not have that. Their water well was drilled about 10 years ago, so any documents associated with it are long gone.

Water testing

Last month, Terrance Wortham called the Victoria County Groundwater Conservation District and the Railroad Commission. Both took samples and began investigations that are ongoing. Wortham also took a sample to an environmental lab in Victoria. He shared the result he got back from that lab with the Advocate, which shared it with Wendy Heiger-Bernays, a clinical professor of public health at Boston University’s School of Environmental Health.

Heiger-Bernays said the type of test performed isn’t one that would prove the Worthams well was contaminated by oil exploration so she “was concerned, but not convinced,” that that was what had occurred.

She said the Worthams shouldn’t drink the water because it had high levels of lead and arsenic. Lead is harmful to everyone, but can especially affect children’s cognitive abilities. Arsenic is a carcinogen.

She noted manganese was also not tested. The presence of manganese could explain the discoloration of the water and it is neurotoxin.

She recommended Terrance Wortham take another sample from his well to test as well as take a sample from his tap.

“Because if the question is, ‘Should I drink this?’ You really want to know what’s coming out of the tap,” Heiger-Bernays said.

Jean-Phillipe Nicot, a civil engineer and a senior research scientist at the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin, agreed.

“If the well water and tap water analyses come back with very different results, that means there is something happening in the pipes,” he said.

Varying explanations

Nicot also offered another possible explanation for the Worthams’ degraded water quality: Hurricane Harvey.

Overall, he said, some have hypothesized the vibrations caused by drilling for oil can move tiny particles in the aquifer, but this hypothesis has never been fully tested.

When asked why, Nicot said, “It would be the same mechanism that would dirty your tap water if the water main in the next street is being worked on. Because it doesn’t happen systematically, researchers would have to guess where it could happen and then it might not, which would be a waste of time and money.”

Jones, Frostwood’s attorney, continued that the oil well couldn’t have contaminated the Worthams’ water because there are thousands of feet of sealing rock between the bottom and any water he uses. He said drilling too close was unintentional as an old map from a prior operator showed Frostwood was complying with the rules.

While Wortham, a long-haul truck driver, wonders whether it’s time to fill up a 5,000 gallon water tank and drive it out to his home on Farm-to-Market Road 616, the landscape of Bloomington changes.

Frostwood alone has 56 wells in Victoria County, and records show some were operated by other companies back in the early ‘90s.

“Frostwood is very definitely revitalizing old oilfields by using the latest industry technology, and without having to use fracking,” Jones said. “Many of these fields have significant resources that could not be recovered using old methods, and that will now be produced using new methods. The whole effort is having a significant and positive economic impact on the area.”

But the Worthams don’t know if it’s worth it.

“I love it out here. This is my favorite place to be,” said Terrance Wortham, who is originally from Houston and moved to Bloomington to get away, not see oil wells everywhere.

“They are throwing them up like it’s Dairy Queen,” his wife added.

Commented