CFD Associate Director Carrie Preston on “Sanctuary: Who Belongs Here”

The Special Collections at the University of Arizona in Tucson currently hosts an exhibition titled “Sanctuary: Who Belongs Here? The Search for Homeland on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1848 to Today.” The exhibition draws from the University’s extensive holdings on the contemporary Sanctuary Movement, which is rooted in faith-based communities along the U.S. southern border, but especially in Tucson, Arizona. On March 24, 1982 Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, led by Reverend John Fife, became the first church in the country to declare itself a sanctuary for Central Americans fleeing persecution in their countries. At its height, more than 200 religious orders and congregations nationwide, alongside universities, municipalities, and religious organizations, including the National Federation of Priests’ Councils (representing more than 33,000 Catholic priests) declared that they were sites of or advocates for Sanctuary.

While in Arizona, I was working with the archives from the so-called Sanctuary Trials of Arizona, which include pre-trial and background materials, court transcripts, clippings from the media, statements from Amnesty International, Church World Service, and other organizations, and audiocassette oral histories from the religious leaders and Tucson refugee support groups. Leaders of the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980’s argued that they were not engaged in civil disobedience or ethical lawbreaking; instead, Sanctuary was a “civil initiative because they were upholding international and domestic laws regarding the protection of refugees that the U.S. government was failing when it deported these refugees. Sanctuary was also upholding the international norm of non-refoulement (refusing to deport people if they would face harm in their own countries). The US government rejected these claims that the Sanctuary Movement was in fact upholding the law and indicted eleven leaders in January 1985, including two Catholic priests and several religious lay workers. They were charged with alien-smuggling, and after a six-month trial in Tucson, eight were convicted of felonies in March 1988. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco upheld the conviction as did the US Supreme Court in 1991. All convicted of felonies received probation.

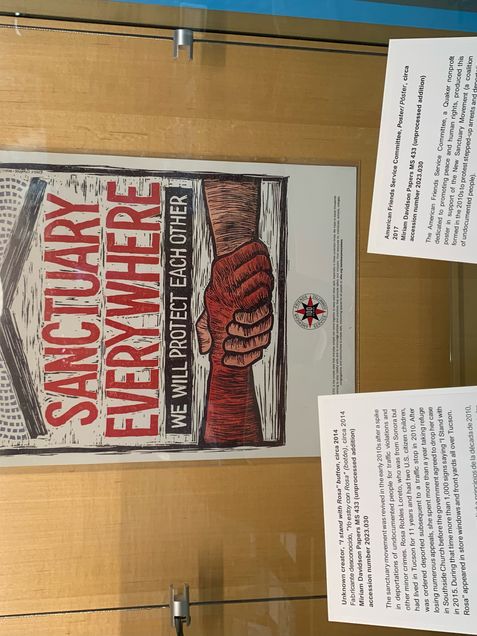

The Sanctuary Movement waned but reemerged in 2007, when the Obama administration stepped up deportations resulting in the removal of over five million migrants. Sanctuary activism succeeded in advancing some protections such as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) that mitigated the deportation of some vulnerable groups. The New Sanctuary Movement continued to work to protect migrants and counter xenophobic messages during the Trump administration and by January 2019, more than 1,100 faith communities had declared themselves part of the New Sanctuary Movement. Cities, including Boston, Cambridge, Newton, and Somerville, and states like Massachusetts have also declared themselves to be migrant sanctuaries – often through democratic voting processes. These jurisdictions seek to send a messages of solidarity with migrants but also indicate opposition to and non-compliance with national policies.