Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 16

Diversity-Focused Undergraduate Premedical Enrichment Programs: The Impact of Research Experiences

Authors Acevedo A, Babore YB , Greisz J , King S, Clark GS, DeLisser HM

Received 22 August 2024

Accepted for publication 11 January 2025

Published 10 February 2025 Volume 2025:16 Pages 205—213

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S489412

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Balakrishnan Nair

Ana Acevedo, Yonatan B Babore, Justin Greisz, Shakira King, Gabrielle S Clark, Horace M DeLisser

Academic Programs Office, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Correspondence: Horace M DeLisser, Academic Programs Office, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Jordan Medical Education Center, 6th Floor, Building 421, 3400 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA, 19104-5162, USA, Tel +1 215-898-4409, Fax +1 215-898-0833, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Many diversity-focused, premedical enrichment programs anchor around a mentored research experience. Data, however, are lacking on how participation in mentored biomedical research in these program impacts participants’ subsequent medical student experience. To begin to address this gap, a cohort of first year medical students who had matriculated through a diversity-focused premedical enrichment programs was queried about the impact of their previous research experiences and their perceptions regarding medical school related research.

Methods: This mixed methods study involved 10 first year medical students from groups underrepresented in medicine (URiM) who had matriculated to the Perelman School of Medical School of Medicine through the Penn Access Summer Scholars (PASS Program) and 10 non-URiM first year peers. At the start of medical school and after their first year, participants completed structured interviews and Likert style surveys to assess the impact of their pre-medical school research experiences and their current beliefs about the significance of research experiences to their medical education.

Results: The quantitative analyses of the survey data demonstrated that the PASS and the non-PASS students were similar in their attitudes, beliefs, and assessments of their research competence. In contrast, qualitative analyses of the interviews offered a more nuanced picture of the differences and similarities between the two groups. The PASS students expressed more confidence in their research skills and felt better able to establish and maintain connections with mentors compared to their non-PASS peers. Both groups of students, however, expressed frustration at the lack of identity-concordant mentors to support their research aspirations and felt the pressure to do research to support their competitiveness for the residency match.

Conclusion: The research experiences of diversity-focused enrichment programs may foster the agency and self-efficacy of participants in ways that support their success in medical school.

Keywords: medical student diversity, diversity recruitment, pathway programs, health equity, health disparities, medical student admissions

Introduction

Initiatives aimed at increasing medical student diversity in the United States have been ongoing for more than 30 years.1–6 These efforts have been varied but have included consideration of race and ethnicity as a part of holistic review during the admission process7–11 and the establishment of diversity-focused, undergraduate, premedical enrichment programs.5,12–14 Although progress has been made with respect to gender,15,16 individuals with minoritized identities, socioeconomic disadvantage and/or a background that is the first generation to attend college, continue to be underrepresented in medical school matriculants and in the physician workforce.16–18 As such, these outcomes speak to the need for continued work to foster medical student diversity. There is, however, concern that the 2023 United States Supreme Court decision constraining the consideration of race in admission to higher education may make this task more difficult.19–21 While presenting a challenge, this decision is likely to foster the development, expansion and refinement of diversity-focused pre-medical undergraduate programs.

There are numerous undergraduate premedical enrichment programs at United States medical schools that aim to increase the numbers of students from groups underrepresented in medicine (URiM) by increasing participant competitiveness and preparedness for medical school, some of which include the opportunity for students to matriculate to the medical school upon completion of the program.22–24 One such program is the Penn Access Summer Scholars (PASS) Program, an early-assurance pre-medical enrichment program established by Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM) at the University of Pennsylvania in 2008.25–27 With a focus on research preparation, personal development and physician identity formation, the program recruits URiM and first-generation and/or low-income (FGLI) undergraduate students from 10 partnering institutions to engage in two consecutive summers of mentored research and a structured enrichment program, with the objective of enabling participants’ successful matriculation to PSOM.

Many diversity-focused premedical enrichment programs are anchored around a robust mentored research experience to foster student agency and self-efficacy, research skills, critical thinking and mentor-mentee relationships. Data, however, are lacking on how participation in mentored biomedical research in a diversity-focused premedical enrichment program such as PASS impacts participants’ subsequent medical student experience. To begin to address this gap, we queried a cohort of first year PASS matriculants on their perceptions about medical school related research and the impact of their summer research experiences through the PASS program.

Methods and Materials

PASS Program Description

The PASS program was established in 2008 by the Office of Admissions at PSOM to increase diversity within the student body by recruiting URiM and FGLI students for a two-summer research experience. Students from 10 partnering institutions (Haverford College, Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr College, Morehouse College, Howard University, Spelman College, Xavier University of Louisiana, Oakwood University, and the STEMMPrep Project of the Distance Learning Center) spend the summer at PSOM after their sophomore and junior years conducting mentored research and engaging in academic and professional enrichment experiences. First year medical students provide near-peer mentoring as well as facilitate and supervise group activities. Program funding is derived from institutional funds and extramural grants. Following completion of the two summers of programming, participants have the opportunity to apply to PSOM for medical school without having to provide an MCAT score. Notably, the program recently transitioned back to being fully in-person in 2022 after being delivered in a virtual format during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.26,27

PASS Programming

Through two, 8-week summer experiences, the PASS program seeks to achieve the following goals:

- Promote a sense of community among the PASS students.

- Foster mentorship between the PASS students and research faculty.

- Facilitate the development of physician identity and professionalism among PASS students.

- Increase exposure to biomedical research and facilitate research skill development.

- Facilitate PASS students’ transition to PSOM.

Participants engage in various program activities for 40 hours per week. Programing consists of research-related activities (25 hours/week), which include conducting research under mentor supervision, online and in-person research skills workshops, and journal club, research and poster presentations. By participating in the program, mentors commit to meeting with students weekly to review the students’ research, to assist the student in preparing research-related presentations, and to advise and support the student during the PASS experience. Additionally, there are enrichment activities (15 hours/week), including podcast and book club discussions, clinical didactics, team-building exercises, physician career narratives, clinical shadowing, weekly reflection sessions, and one-on-one meetings with medical student facilitators and program leaders.26

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Twenty, first-year URiM medical students at PSOM were recruited for this study, including 10 PASS subjects and 10 non-PASS controls. At the start of medical school, participants completed a structured interview that focused on pre-medical school research experiences (Survey 1). Participants were then asked to complete a follow-up interview with the same interviewer a year later (Survey 2). The second interview shifted focus to research experiences in the summer between the first and second year of medical school, as well as any other research experiences and identity interactions in these spaces. Along with each interview, participants completed a web-based, Likert style questionnaire focused on perceived confidence, skills, and competitiveness in research and academic settings. Three of the PASS students did not participate in the study after their first year of medical school. Interview scripts and the surveys can be found in the Supplemental Information.

Study authors were randomly assigned for the interviews of the study participants using online software. All interviews were conducted via Zoom with video recording and live transcription. The transcripts were cleaned, de-identified, and uploaded with the recordings to a University of Pennsylvania web-secure site.

Data Analysis

Upon completion of data collection, interviews were independently analyzed by four authors (AA, YB, JG, SK) via inductive coding.28 Common themes and subthemes were identified and compared between the controls and subjects.

Complete case analysis was used to assess differences in response to Likert-style survey questions. Mann Whitney U testing was used to compare responses between PASS and non-PASS students, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare differences in responses between the same group (PASS or non-PASS) from the first interview to the second. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and determined to be exempt based on minimal risk to participants. Informed consent was obtained from each student prior to their participation in the study, which included publication of anonymized responses/direct quotes.

Results

Demographics of Study Participants

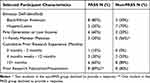

Demographics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. For the 10 PASS participants, eight identified as Black or African American, two identified as Hispanic/Latino, six identified as first-generation and/or low-income, and three reported having at least one family member who was a physician. For the non-PASS students, three identified as Black or African American, seven identified as Hispanic/Latino, two identified as first-generation or low-income, and five reported having at least one family member who was a physician.

|

Table 1 Selected Participant Characteristics (Self-Reported) |

Both groups reported a similar level of research experience prior to participation in the study, with 10%, 30%, and 60% of PASS students reporting 0–3 months, 4–12 months, or 13+ months of prior research experience, respectively, compared to 0%, 20%, and 80% for non-PASS students. Additionally, 89% of PASS students reported a prior research publication or presentation, similar to the 80% of non-PASS who had the same experience. Additional baseline characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Quantitative Analyses of Personal and Professional Attitudes Toward Research

Analysis of participant responses to Likert questions both before and after the first year of medical school querying various aspects of personal and professional attitudes toward research found that both groups were largely similar (Tables 2 and 3). The one area of difference was on survey 2 where it was noted that the research process was significantly less intimidating for PASS participants compared to their non-PASS peer controls, although this only barely reached significance (3.9 vs 2.7, p = 0.0495).

|

Table 2 Responses to Survey 1 Likert-Style Questions |

|

Table 3 Responses to Survey 2 Likert-Style Questions |

Qualitative Analysis of Personal and Professional Attitudes Toward Research

Coding of interviews provided a further understanding of individual research experiences before and during the initial years of medical school. Four main themes emerged from the qualitative analysis, which are discussed further below.

Theme 1: PASS Students Expressed More Confidence in Their Research Skills Than Their Non-PASS Peers

Confidence in research skills was a major finding that differed between the PASS and non-PASS students. Of the interviews coded, 10 PASS participants versus 3 non-PASS participants expressed confidence in their research skills. A PASS student during their first interview noted:

I do remember leaving that first summer way more confident in my ability to just conduct experiments in general, maybe not be on my own, but to run experiments… I do remember leaving feeling very confident. And I remember feeling on top of the world, honestly.

This contrasts with the non-PASS peers who expressed feelings of apprehension:

I still felt very unprepared. For research… both from knowing what to do [and] from… an empowerment standpoint.

Theme 2: PASS Students Felt Better Able to Establish and Maintain Connections with Mentors

A second major theme that emerged from our analysis focused on the ability of PASS students to create and maintain meaningful relationships with their mentors. Both groups indicated understanding the significance of mentorship. However, none of the PASS participants versus 5 non-PASS participants expressed difficulty in maintaining relationships with mentors.

PASS students were able to leverage their experience during the past summers to create connections:

The most concrete way PASS has helped is with the kind of relationship [I have with my mentor]… Going into Penn knowing a faculty member that I can go and talk to is a great support for me.

This contrasted with their non-PASS peers that expressed difficulty finding and connecting with mentors:

Close mentors? I’m not sure. There are definitely people that I know I could talk to if I need guidance on things… But I’ve never really tried [to reach out to them]. I don’t feel like I’m very close to any of them and I haven’t really tried to ask them that much about career advice [like that].

Theme 3: PASS and Non-PASS Struggle to Find Identity-Concordant Mentors

Our findings, however, do illustrate the challenges in finding racially or ethnically concordant mentors in traditionally competitive specialties for both PASS and non-PASS participants in an institution such as PSOM. Participants described having a limited number of people to reach out to and even after identifying potential mentors, and not being successful in establishing these relationships.

For oncology, there wasn’t… a single… Latino oncology staff member in the entire university system. (PASS participant)

I don’t think there was a single Hispanic person on [on the list of orthopedic faculty]. Yes, I can’t really say that I’ve found one yet. (Non-PASS participant)

Theme 4: Both PASS and Non-PASS Participants Had Similar Motivations for Research, Including Significant External Pressure, Particularly in Anticipation of Increasing Their Competitiveness for Residency Programs

Across both PASS and non-PASS groups, participants identified resume building for residency as a strong motivation for involvement in research. This was driven by a belief that increased research productivity would enable a more competitive applications and an increased likelihood of achieving a desired outcome in the residency match.

And also, because I think (research) would build a very strong application going into residency. I have a strategic mindset of, I know that I need publications, research and mentors under my belt. (PASS participant)

[I am] not particularly passionate (about research). If it wasn’t pretty much a requirement for residency, I don’t know if I would do it. (Non-PASS participant)

There is a pressure to produce a number, a quantity of publications, regardless of effort, or how much time you’re spending on them just so you can pad your numbers… I think there is a pressure to seek a particular kind of research, just so you can put a certain number on your application. (Non-PASS participant)

Discussion

Medical student diversity across a broad range of backgrounds and experiences enriches the student experience, fosters cultural and structural competence, and serves to prepare students to better engage the diversity of people they will encounter in their future patients and care teams.21 Further, in several interdependent ways, diversity of the physician workforce, particularly with respect to racial, ethnic and linguistic diversity, fosters trust in the health care system,29–31 enhances patient satisfaction and the quality of the patient experience,29,32–34 enables the inclusion of minoritized and marginalized voices in institutional policy making,35–37 and may improve the patient outcomes for minoritized populations,38–46 although there is debate about this assertion.47–49 The need for a diverse physician workforce will become even more compelling as the demographics of the United States population continues to change.50–53 In this context, premedical enrichment programs focusing on URiM/FGLI students such as PASS have been increasingly used to foster medical student and ultimately physician diversity, but surprisingly have been understudied in the literature. This paper aims to begin to fill that gap by describing the perspectives of a first-year cohort of PASS students regarding the impact of their summer research experiences and the significance of research to their future careers.

The quantitative data from the surveys demonstrated that the PASS and the non-PASS students were very similar in their attitudes, beliefs, and assessments of their research competence, with students generally rating themselves favorably (rating > 3) (Tables 2 and 3). This is not necessarily surprising given that majority of both PASS and non-PASS students had more than 12 months of research experience (Table 1). Interestingly, for both groups of students, the year of medical school experiences did not change these assessments of themselves.

While the survey data did not indicate significant differences between the PASS and non-PASS students, our qualitative data suggest there may be some nuanced differences between the two groups related to the PASS experience. The reasons for this discordance are not clear but may reflect the small size for the quantitative portion of the study. Two themes emerged from the qualitative analyses of the interviews that speak to two goals of the PASS program. First, relative to their non-PASS peers, PASS matriculants expressed more confidence in their research skills (Theme 1). This finding aligns with the program goal of exposing PASS participants to high-quality biomedical research and the development of pertinent research skills and are consistent with a previous study where, in an immediate post-program survey, participants’ self-reported competence in their ability to do research increased significantly after their summer of virtual PASS programing.26 We believe the development of competence and confidence in doing research fosters agency and self-efficacy that help to mitigate minority-related psychological stress such as imposterism.54,55

Second, the PASS matriculants, compared to their non-PASS peers, indicated they were better able to establish and maintain connections with mentors (Theme 2). This finding references the program goal of fostering the mentor/mentee relationship between the PASS participants and their supervising research faculty, where meaningful engagement with the student is an explicit expectation of participation in the program. These data also align with what was reported by Zhou et al where PASS program participants rated their relationship with their mentor as excellent to outstanding.26 Given the importance of mentoring to student success,56–59 the mentor-mentee relationship established through PASS as well as the putative enhanced ability of PASS participants to forge mentor–mentee relationships, together may support the success of these students in medical school. These outcomes likely take on added significance given the underrepresentation of historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups in medicine60 and the consequent difficulty of finding identity concordant mentors as was highlighted by both PASS and non-PASS students (Theme 3).

While the focus of our study was on the impact of the research component of PASS, the interviews yielded additional information regarding student concerns that further contextualizes the significance of the research experience as well as assist in its iteration. With pre-clerkship curricula in most medical schools being Pass/Fail, and the United States Licensing Medical Exam (USLME) Step 1 exam also now Pass/Fail, research and research publications have taken on increased value as a means of enhancing competitiveness for residency training, particularly for competitive specialties and/or top-tier training programs. This is illustrated by data from 2022 where the number of publications by applicant for residency training in plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery, and otolaryngology was, respectively, 28.4, 16.5, and 17.2 compared to 4.1 and 6.8, respectively, for applicants to family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology.61 It is therefore not surprising that we identified as a fourth theme from the analysis of the interviews that both PASS and non-PASS students felt pressure to engage in research to enhance their competitiveness for residency training. The appropriateness of these trends as measures of preparedness for clinical training, their potential for promoting racial and ethnic disparities within competitive specialties, and their impact on learner well-being, particularly that of URiM students, are the subject of ongoing discussion and debate62,63 but are beyond the scope of this paper. However, if the weight given medical student research and publication is taken as a given, the suggested ability of PASS to increase participants confidence and competence in their research skills as well as their ability to develop productive mentor–mentee relationships may foster the competitiveness of PASS participants for highly sought after specialties and/or residency training programs. Such outcomes may speak to a further benefit of the research component of the pre-medical undergraduate enrichment programs targeting minoritized or marginalized individuals.

Conclusion

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, its focus on a single program and a single institution, and the absence of data related to longer term student outcomes such as medical school research experiences, publications and residency outcomes. Consequently, the generalizability of our findings needs to be confirmed with larger cohorts of students who have participated in other diversity-focused enrichment programs beyond PASS and are attending other medical schools beside PSOM. Despite these limitations and the clear need for more work, this paper makes an important initial contribution to the literature aimed at understanding the processes that enable the effectiveness of undergraduate, diversity-focused, premedical enrichment programs.

Data Sharing Statement

De-identified transcripts of the interviews of the study participants can be accessed at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/y7h643hbmj/1. The corresponding author can be contacted for requests for other information.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff and faculty at PSOM and its partnering institutions that helped make the PASS program possible.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Hill K, Raney C, Jackson K, et al. A new way of evaluating effectiveness of URM summer pipeline programs. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:863–869. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S293744

2. Muppala VR, Prakash N. Promoting physician diversity through medical student led outreach and pipeline programs. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(2):165–168. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.08.004

3. Reilly JM, Greenberg I. An 8-year review of match outcomes from a primary care pipeline program. Fam Med. 2023;55(10):646–652. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.297644

4. Stephenson-Hunter C, Strelnick AH, Rodriguez N, Stumpf LA, Spano H, Gonzalez CM. Dreams realized: a long-term program evaluation of three summer diversity pipeline programs. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):512–520. doi:10.1089/heq.2020.0126

5. Stewart KA, Brown SL, Wrensford G, Hurley MM. Creating a comprehensive approach to exposing underrepresented pre-health professions students to clinical medicine and health research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(1):36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.12.003

6. Minen MT, Aymon R, Yusaf I, et al. A critical systematic review assessing undergraduate neurology pipeline programs. Front Med Lausanne. 2023;10:1281620. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1281620

7. Thomas BR, Dockter N. Affirmative action and holistic review in medical school admissions: where we have been and where we are going. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):473–476. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002482

8. Aibana O, Swails JL, Flores RJ, Love L. Bridging the gap: holistic review to increase diversity in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1137–1141. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002779

9. Conrad SS, Addams AN, Young GH. Holistic review in medical school admissions and selection: a strategic, mission-driven response to shifting societal needs. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):1472–1474. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001403

10. Harrison LE. Using holistic review to form a diverse interview pool for selection to medical school. Bayl Univ Med Cent Proc. 2019;32(2):218–221. doi:10.1080/08998280.2019.1576575

11. Dong T, Hutchinson J, Torre D, et al. What influences the decision to interview a candidate for medical school? Mil Med. 2020;185(11–12):e1999–e2003. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa237

12. Wilson-Anstey EA. Effectiveness of the travelers summer research fellowship program in preparing premedical students for a career in medicine. 2016.

13. Achenjang JN, Elam CL. Recruitment of underrepresented minorities in medical school through a student-led initiative. J Natl Med Assoc. 2016;108(3):147–151. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.05.003

14. Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Improving underrepresented minority medical student recruitment with health disparities curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):82–85. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1270-8

15. Figure 12. Percentage of U.S. medical school graduates by sex, academic years 1980–1981 through 2018–2019. AAMC. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/figure-12-percentage-us-medical-school-graduates-sex-academic-years-1980-1981-through-2018-2019.

16. Yoo A, Auinger P, Tolbert J, Paul D, Lyness JM, George BP. Institutional variability in representation of women and racial and ethnic minority groups among medical school faculty. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2247640. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.47640

17. Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the national medical student body—four decades of inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661–1668. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr2028487

18. Campbell KM, Tumin D, Infante Linares JL, Porterfield L, Kisel T. Changing missions of medical schools and trends in medical student diversity. Fam Med. 2023;55(7):481–484. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.928475

19. Boumil MM, Beninger P, Curfman GD. The US supreme court and affirmative action: the negative impact on the physician workforce. Clin Ther. 2023;45(10):1004–1007. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.08.008

20. Montgomery Rice V, Elks ML, Howse M. The supreme court decision on affirmative action—fewer black physicians and more health disparities for minoritized groups. JAMA. 2023;330(11):1035–1036. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.15515

21. Hamilton RH, Rose S, DeLisser HM. Defending racial and ethnic diversity in undergraduate and medical school admission policies. JAMA. 2023;329(2):119–120. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.23124

22. Summer Premedical Academic Enrichment Program (SPAEP) | Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion | University of Pittsburgh. Available from: https://www.medschooldiversity.pitt.edu/our-programs/summer-premedical-academic-enrichment-program-spaep.

23. Early Medical School Selection Program | Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. Available from: https://www.bumc.bu.edu/camed/about/diversity/emssp/.

24. Premedical Urban Leaders Summer Enrichment (PULSE) | Cooper Medical School | Rowan University. Available from: https://cmsru.rowan.edu/diversity/pipeline-programs/pulse.html.

25. Special Programs | MD Admissions | Admissions | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Available from: https://www.med.upenn.edu/admissions/special-programs.html.

26. Zhou C, Okafor C, Hagood J, DeLisser HM. Penn access summer scholars program: a mixed method analysis of a virtual offering of a premedical diversity summer enrichment program. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1905918. doi:10.1080/10872981.2021.1905918

27. Zhou C, Okafor C, Greisz J, Ryu HS, Hagood J, DeLisser HM. Psychological and emotional experiences of participants in a medical school, early assurance admissions program targeting students from groups underrepresented in medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2024;116(1):24–32. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2023.11.012

28. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

29. Moore C, Coates E, Watson A, de Heer R, McLeod A, Prudhomme A. “It’s important to work with people that look like me”: black patients’ preferences for patient-provider race concordance. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;1–13. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01435-y

30. Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071–4111. doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

31. LaVeist TA, Pierre G. Integrating the 3Ds—social determinants, health disparities, and health-care workforce diversity. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):9–14. doi:10.1177/00333549141291S204

32. Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583

33. Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296–306. doi:10.2307/3090205

34. Gross R, McNeill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P. The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians’ perceptions of their patients. Women Health. 2008;48(2):123–144. doi:10.1080/03630240802313464

35. Wingard D, Trejo J, Gudea M, Goodman S, Reznik V. Faculty equity, diversity, culture and climate change in academic medicine: a longitudinal study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(1):46–53. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2018.05.004

36. Acosta DA, Lautenberger DM, Castillo-Page L, Skorton DJ. Achieving gender equity is our responsibility: leadership matters. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1468–1471. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003610

37. Simonsen KA, Shim RS. Embracing diversity and inclusion in psychiatry leadership. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;42(3):463–471. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2019.05.006

38. Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21194–21200. doi:10.1073/pnas.1913405117

39. Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(34):8569–8574. doi:10.1073/pnas.1800097115

40. Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383–392. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006

41. Schulman Kevin A, Berlin Jesse A, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902253400806

42. Kurek K, Teevan BE, Zlateva I, Anderson DR. Patient-provider social concordance and health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective study from a large federally qualified health center in Connecticut. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(2):217–224. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0130-y

43. Adriano F, Burchette RJ, Ma AC, Sanchez A, Ma M. The relationship between racial/ethnic concordance and hypertension control. Perm J. 2021;25:

44. Garg T, Antar A, Taylor JM. Urologic oncology workforce diversity: a first step in reducing cancer disparities. J Urol Oncol. 2022;40(4):120–125. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.04.025

45. Hassan AM, Ketheeswaran S, Adesoye T, et al. Association between patient-surgeon race and gender concordance and patient-reported outcomes following breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023;198(1):167–175. doi:10.1007/s10549-022-06858-z

46. Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. JCO. 2016;34(24):2874–2880. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658

47. Otte SV. Improved patient experience and outcomes: is patient–provider concordance the key? J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221103033. doi:10.1177/23743735221103033

48. Miller AN, Todd A, Toledo R, Duvuuri VNS. The relationship of ethnic, racial, and cultural concordance to physician–patient communication: a mixed-methods systematic review protocol. Health Commun. 2023;38(11):2370–2376. doi:10.1080/10410236.2022.2070449

49. Zhao C, Dowzicky P, Colbert L, Roberts S, Kelz RR. Race, gender, and language concordance in the care of surgical patients: a systematic review. Surgery. 2019;166(5):785–792. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2019.06.012

50. The US will become “minority white” in 2045, Census projects. Brookings. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/.

51. Bureau UC. Older People Projected to Outnumber Children for First Time in U.S. History. Census.gov. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html.

52. Hamidi M, Joseph B. Changing epidemiology of the American population. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35(1):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2018.08.001

53. Alba R, Maggio C. Demographic change and assimilation in the early 21st-century United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(13):e2118678119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2118678119

54. Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok-Syer SS, Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):116–124. doi:10.1111/medu.13956

55. Chrousos GP, Mentis AFA. Imposter syndrome threatens diversity. Science. 2020;367(6479):749–750. doi:10.1126/science.aba8039

56. Henry-Noel N, Bishop M, Gwede CK, Petkova E, Szumacher E. Mentorship in medicine and other health professions. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(4):629–637. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1360-6

57. Burgess A, van Diggele C, Mellis C. Mentorship in the health professions: a review. Clin Teach. 2018;15(3):197–202. doi:10.1111/tct.12756

58. Morte K, Nelson D, Marenco C, et al. Gender differences in medical specialty decision making: the importance of mentorship. J Surg Res. 2021;267:678–686. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2021.06.012

59. Huang D, Childs E, Uppalapati AV, Tai EC, Hirsch AE. Medical student leadership in the student oncology society: evaluation of a student-run interest group. J Cancer Educ. 2022;37(6):1629–1633. doi:10.1007/s13187-021-02000-7

60. Kamran SC, Winkfield KM, Reede JY, Vapiwala N. Intersectional analysis of U.S. medical faculty diversity over four decades. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1363–1371. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr2114909

61. National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: senior Students of U.S. Medical Schools. National Resident Matching Program; 2022.

62. Salehi PP, Azizzadeh B, Lee YH. Pass/fail scoring of USMLE step 1 and the need for residency selection reform. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):9–10. doi:10.1177/0194599820951166

63. Elliott B, Carmody JB. Publish or perish: the research arms race in residency selection. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(5):524–527. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-23-00262.1

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Barriers to Recruitment and Retention Among Underrepresented Populations in Cancer Clinical Trials: A Qualitative Study of the Perspectives of Clinical Trial Research Coordinating Staff at a Cancer Center

Yousafi S, Rangachari P, Holland ML

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2024, 16:427-441

Published Date: 1 November 2024